The early days of my problem are told in my pages

Cycle Therapy and you might like to click on this

link first. This account is designed simply to help others who may be treading the same later.

For those who want it there is plenty of help available. In particular the

NICE full guidlines are well written, clear and should correspond to your treatment.

Levels of prostate cancer are at least easy to measure by the PSA test - a simple blood

test that anyone can ask for from their GP. It takes a minute and you get the results back in a week.

If you type "PSA curve" into Google Images you get a measily number of replies most of which are

not PSA curves at all. Consultants must see so many, or at least look at many lists of numbers,

but for patients it is not so easy to find other peoples. I expect its "patient confidentiality".

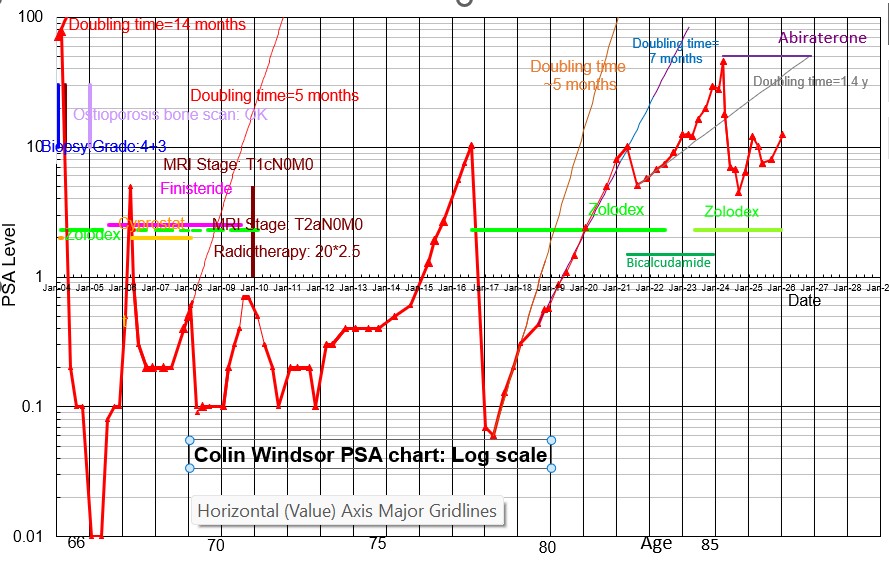

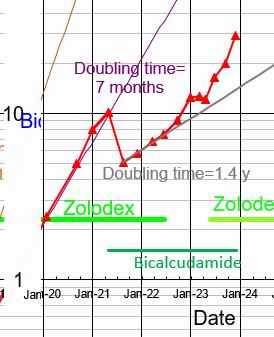

Well at the head of this page is mine for all to see. Note that it is on a logarithmic

scale so that each horisontal line corresponds to a factor of 10.

It shows at a glance a nice summary of my case over the years.

Look first at the top left of the curve before any treatment.

The PSA level of about 80 is quite high and the feint red line indicated the modest doubling time

of 14 months. It's easy to follow such a curve backwards in time. It could have had a levels of

40, 20, 10 and 5 at times 9, 18, 27 and 36 months back. So a visit to my GP any time in the

last three years would have been picked up. (Normal is about 4) "Early" cancers are much

easier to treat than my "late" one.

Looking back over those early days, I have nothing but praise for my GP who has watched carefully over me all these years and for the staff at the Churchill Hospital which has guided my treatment. First they collected data.

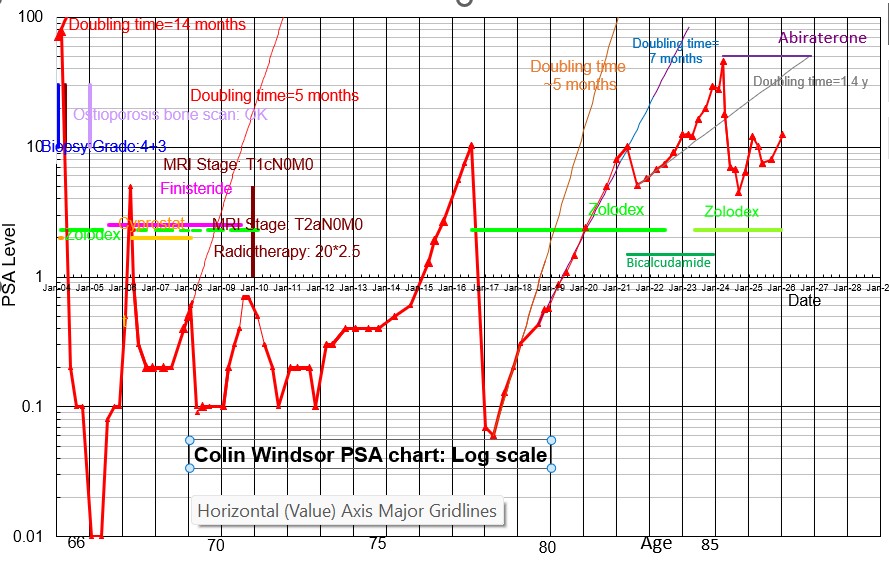

For me the first thing was a digital rectal examination. My GP's gentle finger felt the outside of the prostate and looked for tell-tale hard lumps. The examination can lead to an estimated clinical "stageing" of the cancer. It is written "TnM". T stands for tumour, n is a number 1,2,3 4 with T1: the best type, when no hard lumps are felt the tumour. If a lump is felt just on one side it is T2a if small and T2b if larger. If it is felt on both sides, or over more than half of one side it is T2c. T3 means that the lump extends beyond the prostate. T3a is just beyond the prostate but not into the seminal vesicles, T3b when it does extend. T4 means that it extends to adjacent areas of the pelvis beyond the vicinity of the prostate. The letters NM stands for the degree of spreading. N0 means no spreading to the pelvic lymph nodes and N1 a spread. M0 means no spread beyond the prostate, and M1 that is had spread. My examination was not unpleasant except that he soon found a quite extensive hard lump in the prostate making me T1.

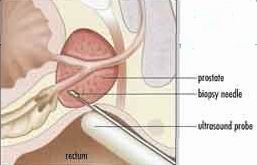

Next was a "biopsy". This is not nice as tiny hollow needles, guided by

ultrasonic pictures, collect samples through the prostate (via the back passage wall).

My Gleason grade was 4+3: mildly aggressive. The first number is the worst needle result and

the second the next worst on a scale from 1 (good) to 5 (bad). They judge the grade from the

appearance of the cells under the microscope. They then combine the two number together to

get a 0 to 10 scale although they are often left un-added.

This first result was so bad that I was immediately started on the hormone treatment I describe later.

This was because with my PSA of 80 and the hign Gleason grade it was highly likely that the cancer

had spread over the body (that is become "metastatic", and important word for cancer sufferers.

This first result was so bad that I was immediately started on the hormone treatment I describe later.

This was because with my PSA of 80 and the hign Gleason grade it was highly likely that the cancer

had spread over the body (that is become "metastatic", and important word for cancer sufferers.

We can indeed at this stage all look up or chance of being metastatic. The Partin tables were compiled by a US doctor Partin from the histories of many patients. You can get a simple on-line table and enter your PSA level, your Gleason score and your staging. Mine came up with only a 30% change of being confined to the prostate. This should rule out surgery and radiotherapy as options, as if it has spread outside the prostate it is still going to be there amd growing after the surgery. So I was started immediately on hormones, of which more later. The bad news was the the Churchill's own excellent booklet on prostate cancer predicted a 30 month life expectancy for my PSA level and Gleason score.

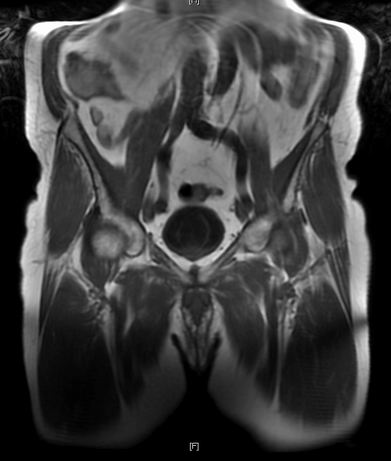

A second diagnostic is the Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan. The unit is a big hollow

magnet into which you are wheeled on a trolly couch. For half and hour or so you hear loud clicks

as the magnetic fields and their gradients are switched around to resonate a radio frequency

signal at particular bits of your inside to the energy spacing between some hydrogen

energy levels which are split by the field. The contrast comes from the different environments

of each hydrogen atom in different types of our tissue. Actually it is the relaxation rate of the

spin of the atoms to their environment which is characteristic of the tissue.

Cancers are active areas and show up as dark in the the picture.

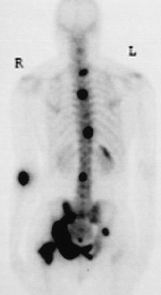

A third diagnostic sensitive in the task of searching for matastatic cancer is "Skeletal Scintigraphy".

A short-lived radioactive isotope such as technitium is injected into the blood, and after an hour

or so the gamma rays emitted by the isotope are captured by large counters which are able to infer the

postion in the body where the technitium lodged. If there is some metastatic cancer lodged in say the

bones this shows up as a dark region. My scan turned out to be benign with "no evidence of any

bony metastatic desease."

In my case when all the diagnostics were done, I had a meeting with my consultant. There is always

this crucial time for any patient when decisions for the future have to be made.

The consultant should be able to come up with a "presenting PSA", a "Gleason score" and a "clinical stage".

Together these are able to define your degree of risk and hence your treatment options.

The NICE definitions are

(i) Low-risk - PSA < 10 ng/ml and Gleason score = 6, and clinical stage T1-T2a

(i)Intermediate-risk - PSA 10-20 ng/ml, or Gleason score 7, or clinical stage T2b or T2c

(iii) High-risk - PSA > 20 ng/ml, or Gleason score 8-10, or clinical stage T3-T4

With a presenting PSA of 66 ng/ml I was solidly in the "high-risk " definition.

With prostate cancer the options of often not simple. Most treatments have pros and cons.

(i) "Watchful waiting" can be a sensible option as all the more radical treatments are likely to

reduce your quality of life. An important benefit in these days of rapid progress is that in so many years

a much better treatment may become available!

This option can easily come round a second time as the first treatment

shows signs of failing. "Wait till your PSA gets a bit higher" came from my consultant after 5 years on

the hormones. But I was always happier when something was being done, and did not take his advice.

(ii) Radical surgery is a serious operation when the whole prostate is removed.

They will usually only do only for low risk patients who have a low probability of having cancer spread

outside the prostate - otherwise your problems will soon return. . Unfortunately the

nerves to the penis are wrapped around the upper capsule of the prostate and are damaged

for around 50% of people.

The euretha goes right through the middle of the prostate and so problems with the waterworks are

not at all uncommon. You come out after the operation with a catheta and they recommend around

a month of convalescence. It costs about £5600.

(iii) Radical radiotherapy can deal with the "medium risk" men with a higher probability of

cancer spread. The radiation can be given to areas just outside the prostate and so is more likely

to be successful for cases of slight spread. The treament means delivering a large radiation dose

to the prostate so that dna damage will result and the cells, both normal and abnormal,

will hopefully not be able to reproduce and will eventually die. They do not die immediately and the length of time before the PSA reaches

a minimum (your "nadir") may be months. Your PSA level at the nadir is a good indicator for the future.

The treatment lasts a month or so and requires daily visits to the hospital every weekday. The radiation

causes unintended damage to organs close to the prostate. In particular the urinary sphincter may

be damaged, as may the bowel. Impotence problems are less common than with surgery but still occur

for some 30%. It costs about £3600.

(iv) Hormones are the treatment of choice for "high risk" patients whose cancer may have spread

outside the prostate. They do not cure the problem but alleviate it by suppressing the activity of the

prostate and stopping its growth. The most common hormone is the injectable LH-RH zolodex.

It requires a short visit to your GP every three months. It has quite different and less drastic

side effects compared to the radical treatments. The loss of

testosterone means that sexual desire is diminished. Performance is affected but not obliterated. Hot

flushes and weight gain are common. Usually the PSA drops very rapidly and your nadir is again

an inportant predictor for a successful future.

After the meeting with myself was a meeting of the "Multi-Disciplinary Team" (MDT), where surgeons, radiologists and oncologists meet together to discuss your case. Its findings are formally kept from us the patients, but asking for information, think is was through my GP lead to some information in my case. They had considered the pros and cons of radiotherapy against hormones. The outcome was that "indication for radiotherapy was uncertain in my case and maybe reserved for locally progressive disease in the future." In retrospect it was a good decision: I was to have a good five years.

In fact my body responded very well to the homones as shown by the factor 10,000 PSA level drop in the first figure. My main drug was Zoladex, the Luteinizing Hormone Releasing Hormone agonist (LH-RH) or (Left Hand-Right Hand). It was given by my GP every three months by injection into my tummy. It is a time-real capsule which lasts for say 3 months. It is very complicated in action. An agonist is a chemical which mimics a naturally occuring one. Thus one occupies the cell receptors in the pituitary gland which produce the luteinizing hormone which stimulates the testicles to produce testosterone. This is does for 10 days or so, but then sticks onto the receptors and blocks the production of any further testosterone from the testicles. To overcome any adverse effects from this "testosterone flare" it is usually supplemented for the first two weeks by another more normal testosterone blocker to, in my case Cyprostat.

There are nasty effects from the hormones. I had regular hot flushes, so that most nights in bed I could no longer snuggle to my wife, but had to stick my legs out from the duvet to cool them! My sexual desire was much reduced, although performance was still there. Girls, you can help enormously by tender stimulation as my dear wife Mo did. Our NHS will provide free viagra to make things work better. Orgasms are still possible, but completely dry, which saves on the sheets! Premature ejaculation is banished for ever.

The downside of the hormones is that they are not a cure. The cancer is still there, just inactive. Nature fights to produce offspring that can survive in this repressed environment. In time new mutated versions will emerge that can grow without the stimulus of testosterone.

One possible way suggested to avoid this is by stopping the hormones as soon as they reached a stable low value and letting the PSA rise again until it reaches some previously agreed level say 5ng/ml. This Intermittent Triple Androgen Blockade has been favoured by Robert Leibowitz in Los Angeles who found encouraging results. The theory is that the cancers shrink, the smaller ones even die, during the homone treatment period of say 13 months. When the hormone treatment eventually ends the PSA will rise, but not to where it was before. My consultant and doctor were quite happy to go along with it although NICE reserves judgement. It is all illustrated in my PSA curve. The zolodex pause began in May 2005, when my PSA was 0.01. In two months it rose to around 0.1 but then stayed stable for some time as the zolodex slowly wore off. It was not until April 2006 that my PSA rose quickly to reach the agreed 5 ng/ml when my doctor put me back on the zolodex. Of course I was disappointed that it did not stabilise below 5 as it had for many of Dr Leibowitz's patients, but then with a presenting PSA of 66 ng/ml I was a high risk patient.

In the months that followed my PSA dropped nicely and stabilised at 0.2. It was 18 months later that I had the news that every patient on the hormones dreads: my PSA was on the rise. I had already lasted over three years so I new that I could not grumble. Every hormone patient soon learns that their cancer cells are still there slowly dividing and one day a mutation will occur that allows a hormone "refractory" mutation to thrive. Over the succeeding six months I carefully plotted the exponential rise of my PSA. It fitted perfectly to the 3-month doubling time shown by the thin red line in my PSA curve. This is quite a rapid rise indicating a nasty cancer (my doubling time bofore treatment was 9 months) My own doctor clearly saw the worst coming and gave me what I knew to be an accurate account of the troubles to come. I remember going to see my consultant in a very depressed state. Cherily he ignored my extrapolations and said that there was lots that could be done. He suggested Casodex, another hormone. But first he said to do one thing at a time, to stop the cyprostat that I had been taking for years. I did this in February 2008 and a surprising miracle happenned. The next PSA taken just a month later was 0.1. I was in disbelief and asked the surgery nurse for a second test, but it was the same. Somehow my mutated cancer cells needed the cyprostat hormone to survive. It was not a hormone resistant cancer but a cyprostat stimulated cancer.

It was back to normal living for nearly a year, but then once again I had an elevated PSA reading

In three months it had doubled from 0.1 to 0.2. Once again my PSA was back to the three-month

doubling time of the previous rise. It is almost as if there were a sea of tiny clusters

of mutated cells quietly growing unseen until their PSA rises above the background level, 0.1 in my

case. I tried stopping the finisteride pills I had been taking for years.

But at next visit to the Churchill in September 2009, I saw a bright young registrar, who was to look after me

very well over the coming months. We talked over many options.

I could go onto the Casodex, but it would take some time to know if it was effective. He actually

suggested waiting to see how things developed. I remembered the quotation above from my first

Multi-Disciplinary Team meeting: "indication for radiotherapy was uncertain in my case and

maybe reserved for locally progressive disease in the future." I said, "Why not this option now?"

He did not say no, but said that I should need to have further MRI and bone scans done to test

that my cancer was not at present metastatic. Radiotherapy would only damage cancers in the

prostate area so that if the cancer has spread anywhere else, the treatment would be an expensive

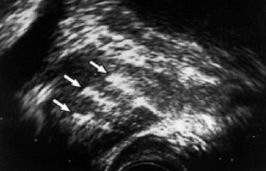

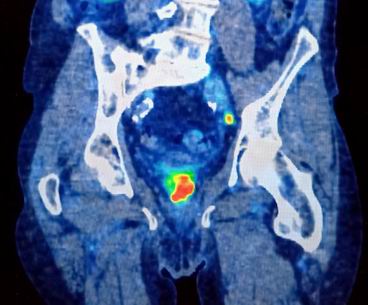

waste of time. The NHS again swung into action. The MRI scan was done next month and turned

out to be fine. This time a splashed out and bought the CD of my images. The image to the right

is my pelvis showing the circular bladder and the prostate beneath it. The registrar went through it with

me and pronounced it OK.

But at next visit to the Churchill in September 2009, I saw a bright young registrar, who was to look after me

very well over the coming months. We talked over many options.

I could go onto the Casodex, but it would take some time to know if it was effective. He actually

suggested waiting to see how things developed. I remembered the quotation above from my first

Multi-Disciplinary Team meeting: "indication for radiotherapy was uncertain in my case and

maybe reserved for locally progressive disease in the future." I said, "Why not this option now?"

He did not say no, but said that I should need to have further MRI and bone scans done to test

that my cancer was not at present metastatic. Radiotherapy would only damage cancers in the

prostate area so that if the cancer has spread anywhere else, the treatment would be an expensive

waste of time. The NHS again swung into action. The MRI scan was done next month and turned

out to be fine. This time a splashed out and bought the CD of my images. The image to the right

is my pelvis showing the circular bladder and the prostate beneath it. The registrar went through it with

me and pronounced it OK.

They did not give me a bone scan. Another meeting in November

gave the all clear for radiotherapy and my first radiotherapy planning visit was booked that month.

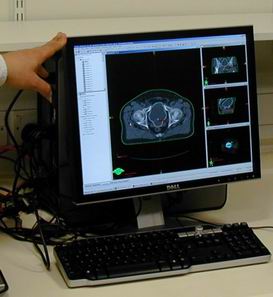

I was pleased and surprised by the detailed planning that goes on before radiotherapy.

After many questions from the nurse, there is a Computer Tomography three-dimensional X-ray scan

which enables the boundary of my particular prostate to be precisely defined. Tiny tatoos on your sides

help to line you up when treatment comes. Computers work to

find the optimal dose distribution to maximise the dose to the prostate and minimise the dose to the

nearby rectum and urinary tract. Generally they arrange "conformal" radiography where the beam comes

from three directions, above, from the left and from the right, all directed at the prostate.

This gives a bigger dose at the prostate for a given dose on the skin.

The outcome of the calculations was a set of specific dates for

the 20 shots of my treatment. It was basically every day for a month but with weekends off

and holidays like Christmas and Boxing day off also. I was to have a total dose of 50 Greys.

It is interesting that a dose of only 6 Greys would kill 50% of people if given all over the

body. The concentration of the dose into the smallest possible area is the key. I did query this

number with the nurse as it is a subtle decision, and the 50 Greys was lower than the NICE

recommendation. The larger the dose the more side effects

you may have, but the longer you may survive! I was surprised to be phoned up by my doctor

at the Churchill to discuss the decision. I was happy to take their judgement.

I was fortunated in that the Churchill had just a few months before opened their grand new cancer "Wing". I was even more fortunate that on the following Saturday, there was an Open Day to celebtrate the opening of this wing and associated University building. It was a lovely opportunity for Mo and I to visit the Centre, look round the radiotherapy equipment, and talk to some of the patients who had finished the treatment.

My first shot was on Tuesday 8/12/09 and I started immediately fell in to a quite pleasant routine of cycling in, having the treatment and going to work. The treatment itself was only about 50 seconds, but the formalities and lining up bring the time in the radiotherapy room to about 15 minutes. The waiting for me was about another 15 minutes, Generally they kept well to their shedules. Then I would cycle back to Culham and do a little work before the cycle home. Apart from a couple of punctures, this schedule worked excellently for the first 9 shots, before the winter weather ended the cycling. December 2009 suddenly turned into a traveller's nightmare. There were many inches of snow, which soon turned into treacherous ice. Cycling became too dangerous, and going in the car was difficult. But somehow I made it into the hospital each day, as did the nurses and the technicians working the machines. I never missed a shot. I give my highest praise to the staff in the Radiography Unit.

An unexpected surprise was the delightful atmosphere

in our radiotherapy waiting room.

All the patients were undergoing much the same unpleasant treatment, and we all tended to come

at much the same times every day. The result was that we soon got to know eachother well and

and I made many firm friends, close enough to be really sad when we had to say goodbye on their last day.

It made such a difference to be greeted each morning by a cheery smile.

I think we were able to help eachother. I certainly was greatly helped by hearing other's detailed experiences.

and how other's managed their symptoms.

The nicest day was a snow-swept Christmas Eve when there were biscuits, nice fruit drinks

and our own Christmas tree to cheer us up.

There were 6 radiotherapy machines in the centre and I was on machine #5 under the able charge of a kind talanted nurse who was to become another good friend. The machine was American and brand new. Laser beams helped the nurses to align you up to just a few millimetres with the help of the tatoos given earlier. Further precision is not much help as things move about with your toilet motions by up to several millimetres. Then the nurses briefly leave you alone and the machine buzzes as it gives you the dose. For several weeks I felt no symptoms whatever. The large dish of moisturising cream which the NHS had provided for me to rub into the sore bits was never used. Indeed I was not sure where to rub it in. But after Christmas the symptoms came. I had diarreara, and certainly felt unusually tired. But soon it was my last day and the treatment was over. It took several weeks to get back to normal.

The followed a long time of waiting to see how the PSA would repond to the treatment. I had come off the hormones the previous November so it was bound to rise eventually. On 17/2/2010 it had gone down to 0.5. At least they had hit the growing cancer! The on 30/4/10 it was down to 0.3, on 30/7/10 to 0.2. It was good as that year in July 2010 I was so busy at work working on the possible detection of Improvised Exposive Devices with holographic radar and indeed explaining it all to our Queen at the 2010 Royal Society Soiree!

On 28/9/10 my PSA reached its nardir of 0.1. Now on 14/9/12 it is rising again. Watch this space!

So nearly a decade has passed and I am still here to update this account. The PSA rise mentioned above slowed right down. On 19/2/13 my new consultant reviewed the situation and decided to sign me off, reviewing my PSA every 6 months, refering back if it rose above 4. I felt fine, In July 2013 my life changed as I started work half time for Tokamak Energy helping to save the planet with clean, safe and abundant fusion energy. My 2015 I was again at the Royal Society exhibiting our on-line demo running our tokamak in Didcot!

My PSA did stay stable for for a year or so but then began to rise slowly again. By 28/4/15 it had reached aroung 1 and was doubling every 5 months. My consultant was relaxed and happy to let it rise till on 12/8/16 it reached 10.3. She then agreed with me that it was time to go on to the hormones once again. It was a sad day as my wife Mo and I had really enjoyed the 6 years of a bit more testosterone! The PSA dropped immediately to below 0.1 but the low values were not to last very long and by 21/8/18 it had reached 0.43. My new Specialist Nurse was happy with it. She regarded the rise as "slow rise" and said to wait until it was above 10. This did not happen till 6/5/21. By then the new world of covid was with us, and coversations with my new consultant were over the telephone. He put me on to bicalutamide, other hormone suppressant, but warned that any reduction would be non-lasting.

In May 2022 I sang at the funeral of a 92-year old scientist who had died of a mixture of prostate cancer, covid and old age! His son vividly described the symptoms of a metastatic prostate - the back pain, and inability to look after yourself. I am to have another X-ray CT scan to check my metastatic status and feel inclined to take any options!

At the end of 2021, the CT scan revealed that the cancer had not spread, and the bicalutamide was clearly working. My PSA dropped from just over 10 to 5.09 and during 2022 it rose only slowly with a doubling time of around 16 months. In July 2022 my consultant said that I may well not die of prostate cancer.

The good news was not to last. On 9/1/23 my PSA was unexpectantly high, suggesting a nasty strong decrease in doubling time. My consultant sent me to have another Computer Tomography X-ray scan and this time the results were not so good. I had a slight increase in the size of two pelvic lympth glands. On the screen they looked small enough but my consultant was worried: it could be the start of matastatis. He wanted further information from Positron Emission Tomography, with the possibility of further radiatherapy if these results were satisfactory.

Only later did it emerge that I did not have a zolodex injection in January 2023 and the rise might have been "flare" as the treatment stopped. Three months later the PSA was flat, and six months later it had reduced. Possibly my cancer had learnt to live with zolodex and stopping it was causing the PSA reduction. Who knows for on 31/5/23 I did have a zolodex injection and the PSA rose rapidly to around the 6 month doubling time before the bicalutamide.

On 25/5/23 on a lovely sunny morning I cycled to the Churchill for the PET scan. They give you a radioactive injection and ask you to isolate from others for a half hour before the scan. Unlike MRI, PET scans are quite quiet and took around 20 minutes. The result shown on the right shows my prostate with the big red signal and the little red and yellow dot North-East is my metastatic pelvic lympth node. The strong signal from the prostate meant the a second radiotherapy was not an option. I had "advanced" metastatic prostate cancer.

In December 2023, my new consultant suggested that I take a new treatment Enzalutamide, if indicated by more CT scans.

In February 2024 the results were all in. The bone scan was quite negative, and the cancer had spread only to the pelvic lymph nodes. My PSA was slightly down to 27.8 after stopping the bicalcutamide. My excellent consultant spoke against Enzalutamide because of it negative effects on cognition, memory, and I did not fancy its reduced balence and probability of falls. So I signed up for Abiraterone, another hugely expensive pill that has less problematic side-effects. They begin with kidney and liver blood tests and a long session with a doctor to discuss possible side effects. They give you a direct oncology patients phone number, and a special card to carry with you. The pills come by special delivery from Bristol! I started on 5/4/24 and have had no discernable problems. After two weeks the PSA level had more than halved to 17.7! Then around a month later it had reached 7! All without side affects. Good news indeed. Interestingly the pills did not arrive at the end of the second month despite a recent blood test and I had 4 days off before a bus ride to the Churchill Pharmacy after many phone calls. I detected no changes from the 4-day "holiday" from the abiraterone treatment.

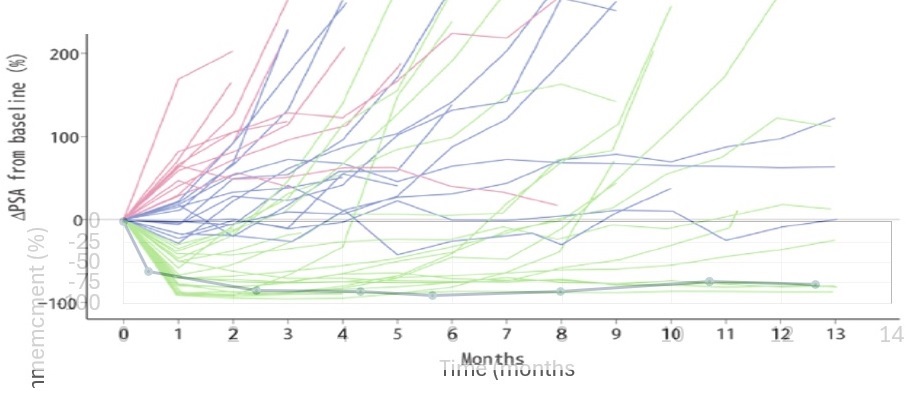

The figure above shows the continued reduction in PSA to a nadir of 4.5 on 23/9/24. It then started rising to reach 12.06 on 24/2/25. Clinical oncology was worried as the doubling time was around 3 months, and it could mean that the Abiraterone was no longer working. I looked up the literature and found a Japanese trial Japanese trial paper, with some data which is shown superimposed on my chart, given by the black lines and circles. I had responded pretty well! There was further good news. A new test was taken on 24/4/25 and showed a slight reduction. I could continue with the treatment. The worries had some good sides. I had a most helpful discussion with a new consultant oncologist on 29/4/25. Olaparib could be a good option.

Now in January 2026, I have another couple of results:not so good. My PSA has risen to 12.5, but more seriously the doubling time is back again to around 8 months. I will be in trouble in a year! But I am feeling fine, apart from a problems with a carcinoma in my left leg which was expertly cut out on New Year's Eve 2025. It was probably caused by the Arbiraterone treatment.

Copyright 2009 Colin Windsor : Last updated 27/01/2026