Profile of Colin Windsor

by Lucinda Kowol published in the NDT Journal(INSIGHT 37,822-3,1995)

Who would have thought seeing Colin Windsor flash past the car park on his bicycle every morning, that he is one of only just over 1,000 scientists who are Fellows of the Royal Society, probably the only one from NDT. The election process is rigorous and long drawn out, with only around 1 in 50 making it past the winning post. Candidates must be proposed by at least six existing fellows, and their published papers scrutinised by subject committees. Only when they have successfully negotiated these hurdles are they able to write their names in the book, which also contains those of Christopher Wren, Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton. Although his parents showed no scientific bent, Colin was lucky to join a lively Science VIth form at Beckenham and Penge Grammar School and, with only eight others in the group, received plenty of individual attention. This paid off when he was offered a Demiship (half a fellowship) at Magdalen, as was the present Institute President, Bill Gardner. Some ten years earlier, Magdalen, with its choir, was also a good college to choose for anyone interested in music and Colin took full advantage of that. He sang in the undergraduate choir, and played the clarinet and guitar. It was at a meeting of the Heritage Club. a folk music group meeting informally in people's rooms, that he met his wife Margaret. She was then up at Somerville, and shared not only his interest in music but also in physics.

Harwell was in those days the obvious and most exciting place for young scientists to work, and Margaret started working there while Colin was taking his DPhil on paramagnetic resonance. Colin remembers the ordeal of his doctorate examination very well. His external examiner was Lord Marshall, then in the Theoretical Physics Division at Harwell. "There are a few times in everyone's life," he said afterwards, "when you need to be stretched to the limit, and this is one of them."

Life for scientists in the 60s was easy by today's standards. You hardly had to knock at doors, as they seemed to open for you. Of course the brighter you were the wider they stood. Like many scientists, Colin Windsor was tempted by life in America and briefly became part of the brain drain when he joined a group led by Professor Werner Wolf at Yale. Colin and Margaret enjoyed America. They lived in a very vibrant Italian neighborhood, hardly turning a hair when there was shooting next door. Kennedy was shot too, but it was not violence that brought them back, but family ties, a job together, and a longing for Marmite and custard (not together)! So both husband and wife were working at Harwell. As they both still do. There, Colin changed his field to neutron scattering, working with Ray Lowde on those well-known technological materials, nickel and iron. But it was not technology, but rather new science to unravel the interactions which caused the magnetism in these 'itinerant' metals (itinerant because the electrons are always hopping from atom to atom). They plotted out a big map of these electronic motions at several temperatures. and fitted it to theory. The map still hangs on his wall.

In the early 70s he was influenced by Peter Egelstaff who firmly believed that the unique nature of neutron scattering measurements, and the easy penetration of neutron beams, would be music in the ears of industrialists. The vision was at least partly true, and Harwell has remained at the forefront of the industrialization of neutrons to this day. The paper he wrote together with Mike Hutchings on the measurement of residual stress using neutrons was one of those mentioned in his citation. It has now become the standard method, at least for calibrating other techniques. He recently spent a three-month stint at Riso in Denmark measuring the stresses in a highly active steel. Unfortunately, measurements using reactors are expensive and hardly portable. This led to his work with Roger Sinclair on developing neutron scattering on accelerator-based sources. He remembers happily the little group he led, building up the new types of instrument that could be made to work on such sources. They won approval for a new electron linac, and he wrote the book, 'Pulsed Neutron Scattering' while it was being built.

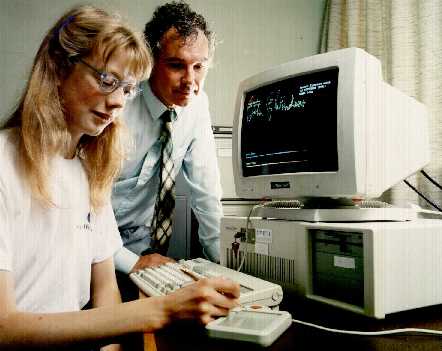

More recently, Colin has been working on the applications of neural networks, a new type of computing where answers are 'remembered' from training data rather than being worked out. Harwell led a European ESPRIT project, and the NDT Centre became involved through a project to classify defects in welds from ultrasonic data using neural networks. It resulted in a demonstrator where you could see the result after scanning a weld in a few seconds and was selected by the EEC to represent ESPRIT at Avignon in 1992.

Following that project came a hectic year working on a system for validating human signatures This is work eminently suitable for neural networks, and so it proved, with AEA now having patented and developed a working system, now on trial with the Employment Services Agency. Because of his experience with neural nets, Colin has recently been working at Culham Laboratory on the difficult task of controlling the position and shape of plasmas. Much of his work involves the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) a truly worldwide project where the Europeans, the Americans, the Japanese and the Russians are for once all working together. When we spoke he had just returned from Garching in Germany, the European centre for ITER.

A quietly spoken man, Colin is modest about his very considerable achievements, although he evidently enjoyed his initiation at the 'very grand' premises of the Royal Society at Carlton House Terrace. His usual methods of relaxation are less ostentatious. He enjoys singing and composing music and was for many years choirmaster of Goring Church. He likes sketching, especially faces. In fact, he holds a patent for a system of face recognition, which he developed, from the signature work. Essentially, it makes a quick sketch of the subject in just a few strokes, and his only regret is that pressures of work in today's Harwell cause it to languish in a box file undeveloped.

Copyright 2004: Colin Windsor: Last updated 5/10/2004