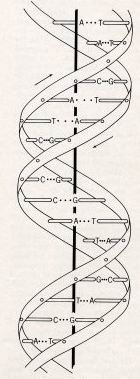

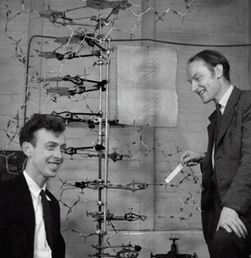

The elegant structure of DNA unravels for us two of the great mysteries of life - how our cells

multiply, and how our Dad's sperm and our Mum's egg make us into a unique person. The figure is from

Crick and Watson's 1953 paper. The caption says: "This figure is purely diagrammatic. The two ribbons

symbolize the two sugar-phosphate chains, and the horizontal rods the pairs of bases holding the

chains together." Later the paper famously says: "It has not

escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggest a possible

copying mechanism for the genetic material."[1].

The elegant structure of DNA unravels for us two of the great mysteries of life - how our cells

multiply, and how our Dad's sperm and our Mum's egg make us into a unique person. The figure is from

Crick and Watson's 1953 paper. The caption says: "This figure is purely diagrammatic. The two ribbons

symbolize the two sugar-phosphate chains, and the horizontal rods the pairs of bases holding the

chains together." Later the paper famously says: "It has not

escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggest a possible

copying mechanism for the genetic material."[1].

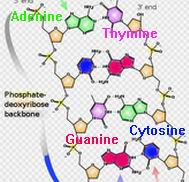

There are two interlacing spirals, red and blue and kept at 12 and 0 Volts in the lamp. The two chains are complimentary since they are linked by two sets of complimentary "bases". These are Guanine (red) which links to Cytosine (blue) and Adanene (green) which links to Thymine (cyan). The links are quite weak through hydrogen bonds (shown by the dashed lines in the light). This allows mitosis - for the DNA molecule to replicate by splitting the two chains and letting free bases go to the corresponding complementary molecule. It also allows for fertilisation with the mixing of DNA from the sperm and the egg to make new DNA with portions from both parents.

The light is more or less to scale at 1 Anstrom unit =1 cm, or 1 nm=1 =10 cm, or 1 to 100,000,000.

The radius of the helices are about 20 A, the periodicity of the helix is about 34 A and there are

10 base pairs per helical turn making the spacing of the base pairs 3.4 A.

However the helical chains are incredibly long on this scale. The human Y chromosome has 58 million base

pairs, and if stretched out would be 58x106x3.4x10-8=2.0 cm long!

The helices were made from 1 cm copper pipe left over from the solar water heating. The base pairs were cut from quality (but expensive at £20) plastic sheet from FOCUS. The model is two revolutions long so contains 21 base pairs. The order of the bases on either of the helices define the genetic code. Each pair can be one of the four: Guanine (red), Cytosine (blue), Adanene (green) or Thymine (cyan). In the light these are represented by corresponding LED colours, one on each distinct base.

The order of the basis defines a code, nature's code for each of us. Each base defines one of four yes/no choices, or four 1/0 choices or four bits. In life they are grouped into sets of three base pairs - the codons. These define up to 4x4x4 yes/no choices, or 64 bits, or 8 bytes. The 64 bit codons are then translated by messenger RNA into amino acid chains which in turn make specific proteins. In our light coding, instead we use the same 3-pair codons to translate into the 26 letters of the alphabet. The order of the 21 bases on the light does in fact make up a 7-letter word which you may find out for yourself with enough detective work!

The LED lights were bought from www.besthongkong.com They all ran nominally at 0.020 amps but they seemed too bright for the bases so I ran them at 005 amps. Each colour had different nominal voltages, red at 2.0 V, blue and cyan at 3.3V and green at 3.5. Each LED was part of a chain of 5 so that the total nominal voltage was about 15V. It was like Soduko - you fiddle the starting point and cross-over point until the sum of the voltages for each of the colours adds up to near this value. The final adjustment is made with an added resistor of around 100 ohms. In the table one LED string is shown in normal type and one in italic type, thus showing the crossovers. Bold type indicates the beginnings and ends of the strings.

The real point of the light was to provide bright illumination when operating the TV zapper! The lower plate of the

structure contained 21 superbright white LEDs arranged in 7 groups of three lights in series together with a 100 ohm resistor.

They are operated by a separate switch.

| Pair | Codon | Bit | Up | Down | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | Guanine | Cytosine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | - | 2 | Adenine | Thymine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | - | 3 | Adenine | Thymine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 2 | 1 | Cytosine | Guanine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | - | 2 | Adenine | Thymine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | - | 3 | Guanine | Cytosine | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | 3 | 1 | Cytosine | Guanine

| 8 | - | 2 | Cytosine | Guanine

| 9 | - | 3 | Thymine | Adenine

| 10 | 4 | 1 | Adenine | Thymine

| 11 | - | 2 | Thymine | Adenine

| 12 | - | 3 | Cytosine | Guanine

| 13 | 5 | 1 | Cytosine | Guanine

| 14 | - | 2 | Thymine | Adenine

| 15 | - | 3 | Adenine | Thymine

| 16 | 6 | 1 | Cytosine | Guanine

| 17 | - | 2 | Guanine | Cytosine

| 18 | - | 3 | Adenine | Thymine

| 19 | 7 | 1 | Cytosine | Guanine

| 20 | - | 2 | Guanine | Cytosine

| 21 | - | 3 | Thymine | Adenine

| |

How was it found that DNA is so important? It was not always so, and our proteins were long thought to be

the key by which inherited characteristics were transmitted.

It was in 1944 that a 67 year old Canadian Oswald Avery, working in a private

Brooklyn bacteriological institute who found that strains of virulent bacteria were transmitted across

generations by their DNA but not by their proteins [2]. He said in 1943: "If we are right, and of course that is not

yet proven, then it means that nucleic acids are not merely structurally important but functionally active

substances in determining the biochemical activities and specific characteristics of cells and that by means

of a known chemical substance it is possible to induce predictable and hereditary changes in cells.

This is something that has long been the dreams of geneticists."

It started the race to unravel the convoluted secrets of the DNA structure.

It was in 1944 that a 67 year old Canadian Oswald Avery, working in a private

Brooklyn bacteriological institute who found that strains of virulent bacteria were transmitted across

generations by their DNA but not by their proteins [2]. He said in 1943: "If we are right, and of course that is not

yet proven, then it means that nucleic acids are not merely structurally important but functionally active

substances in determining the biochemical activities and specific characteristics of cells and that by means

of a known chemical substance it is possible to induce predictable and hereditary changes in cells.

This is something that has long been the dreams of geneticists."

It started the race to unravel the convoluted secrets of the DNA structure.

Another fundamental step was taken by biochemist Erwin Chargaff who emigrated

from Austria before the war. He worked on DNA in New York at Columbia University

using the new chromatography technique technique of two British scientists, John Martin and Richard Synge.

He showed by studying the compositions of the four bases in several different organisms that the ratio of

of adenine and thymine in DNA were roughly the same, as were the amounts of cytosine and guanine.

This later became known as the first of Chargaff's rules.

This rule was to become key to the successful solution of the structure.

% of Bases in DNA

| Organism | A | T | G | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 30.9 | 29.4 | 19.9 | 19.8 |

| Chicken | 28.8 | 29.2 | 20.5 | 21.5 |

| Grasshopper | 29.3 | 29.3 | 20.5 | 20.7 |

| Sea Urchin | 32.8 | 32.1 | 17.7 | 17.3 |

| Wheat | 27.3 | 27.1 | 22.7 | 22.8 |

| Yeast | 31.3 | 32.9 | 18.7 | 17.1 |

| E. coli | 24.7 | 23.6 | 26.0 | 25.7 |

Chemistry is one thing, but how can a structure on such a tiny scale be found?

The key to the solution was X-ray diffraction.

This was a discovery of the Braggs, Father William and son Lawrence -at 25 the youngest winner of

a Nobel prize. The spacings of atoms may be tiny but so is the wavelength of X-rays. In fact they

are typically 1 Angstrom unit. The X rays scattered by atoms interfere constructively.

The X rays reflect off the planes of atoms in a crystal just as in an orchard the lines of trunks

seem to form a plane. They are called "Bragg planes". Lawrence Bragg was head of the Cavendish Laboratory

in Cambridge in Crick and Watson's time. It was he who encouraged the Cambridge Physics Lab into

determining complicated biological structures. After the war it was difficult for Cambridge to compete

in big science so Bragg started a molecular biology group. He hired John Kendrew and Max Perutz.

whose great success, also in 1953. was the discovery of the struture of haemoglobin.

The X rays reflect off the planes of atoms in a crystal just as in an orchard the lines of trunks

seem to form a plane. They are called "Bragg planes". Lawrence Bragg was head of the Cavendish Laboratory

in Cambridge in Crick and Watson's time. It was he who encouraged the Cambridge Physics Lab into

determining complicated biological structures. After the war it was difficult for Cambridge to compete

in big science so Bragg started a molecular biology group. He hired John Kendrew and Max Perutz.

whose great success, also in 1953. was the discovery of the struture of haemoglobin.

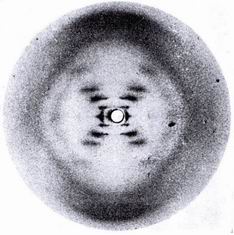

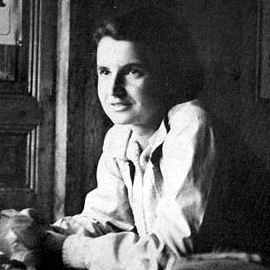

The figure on the left is the X-ray photo of DNA by Rosalind Franklin, the English crystallographer from

King's College London. She worked on DNA with her

boss John Randall, painstakingly preparing the crystals necessary for good results. Her specimens

were from the thymus of a calf with the strands aligned into a fibre the thickness of a human hair. The X

rays looked down the fibre.

Her photographs are among

the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken, were the words of one of our

greatest crystallographers J D Bernal. The horizontal stripes across the picture show the spacing of

the base pairs along the helix. The cross indicates its helical structure and the angle of the cross shows

the pitch of the helix. The diffraction pattern intensities from helical structures had been solved by

Bill Cochran. The intensities follow a Bessel

function: Fn=Jn(2prR) exp(i n(

j+p/2).[3]

She had by 1953 concluded that the structure was a double helix and determined its periodicity and the spacing of the base pairs. She

wrote it all down in a Medical Research Council report that was surreptitiously leaked to Cambridge.

She published her work in the same issue of Nature as Watson and Crick [4].

She died in 1958 from cancer very likely caused by the X-ray doses from her experiments.

Her photographs are among

the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken, were the words of one of our

greatest crystallographers J D Bernal. The horizontal stripes across the picture show the spacing of

the base pairs along the helix. The cross indicates its helical structure and the angle of the cross shows

the pitch of the helix. The diffraction pattern intensities from helical structures had been solved by

Bill Cochran. The intensities follow a Bessel

function: Fn=Jn(2prR) exp(i n(

j+p/2).[3]

She had by 1953 concluded that the structure was a double helix and determined its periodicity and the spacing of the base pairs. She

wrote it all down in a Medical Research Council report that was surreptitiously leaked to Cambridge.

She published her work in the same issue of Nature as Watson and Crick [4].

She died in 1958 from cancer very likely caused by the X-ray doses from her experiments.

But solving structures from diffraction is not easy. All you see are the Bragg spots and their intensities. They cannot be used to determine

a structure because that would require knowledge of the phases as well as the amplitudes. All you can do is assume a structure and

calculate the intensities. This is why "model building" became so central to complex biological structure solutions. The master of this craft

was Linus Pauling, who had long immersed himself in bond lengths and angles. For Christmas 1951, Crick gave Watson a copy of

Linus Pauling's influential book, "The Nature of the Chemical Bond."[5]. "Somewhere in Pauling's masterpiece," Watson remembered,

"I hoped the real secret would lie.". It was his methods which inspired Watson and Crick.

So we come to the Cavendish Physics Lab in Cambridge in 1953. William Bragg is Professor, Crick and Watson share a cramped office

in a hut outside the main building. Also in the office is Pauling's son Peter, a graduate student of Kendrew and Jerry Donohue,

an American from Caltech who had worked for years with Pauling and was expert on hydrogen bonding.

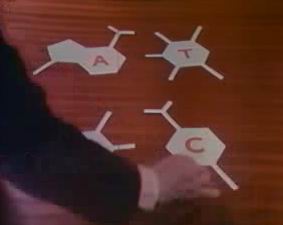

As Watson describes [4], they started building a double helix model

based on the crystallography information, but where do you put the base pairs? They cut out cardboard models of the four bases with their

positions for hydrogen bonds added. Thinking of the Chagaff rules, and the nature of hydrogen bonding, they found that the

adenine/thymine pair and the cytosine/guanine pair both had a very similar size and could be thought of as interchangeable.

They were also reversible so that thymine/adenine was as good as adenine/thymine and guanine/cytosine as good as cytosine/guanine.

It seemed so right as the complementarity automatically gave the key to its mechanism. The disordered ordering of all four bases

gave the necessary code. The story is that they immediately went down to the nearby Eagle pub and announced that they had found

"the secret of life!"

[1] J D Watson and F H C Crick "Molecular structure of nucleic acids", Nature, 4356, 737 (1953): http://www.nature.com/nature/dna50/watsoncrick.pdf

[2] Avery, Oswald T., Colin M. MacLeod, and Maclyn McCarty. "Studies on the Chemical Nature of the Substance Inducing Transformation of Pneumococcal Types". Journal of Experimental Medicine 79, 2 (1944): 137-158.

[3] Cochran, W., F. Crick, V. Vand (1952), "The structure of synthetic polypeptides. I. The transform of atoms on a helix", Acta Crystallographica, vol. 5, 581.

[4] Rosalind E Franklin and R G Gosling, "Molecular Configureation in Sodium Thymonucleate" Nature, 171, 740 (1953): http://www.nature.com/nature/dna50/franklingosling.pdf

[5] L Pauling ,"Nature of the chemical bond",(1939): Cornell University Press

Copyright 2009: Colin Windsor: Last updated 1/5/2009