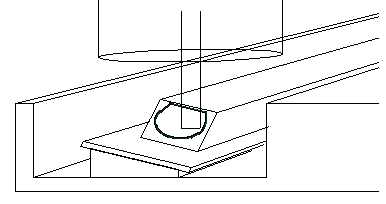

I used the router by making it traverse an

unchanging straight path, and using wedge-shaped pieces of waste wood to hold

the work piece at the right position and angle so that the cutter took the

required path. My father's old bench had a tool recess beneath its working

surface, and I used the outside of this to provide the defining straight edge,

which the router edge guide would slide along as shown in figure 4. Simple 20

degree wedges provided the necessary angles and a

threaded rod through an oval hole provided the lateral adjustment. I used a

mirror to peer down the two ends of the recorder blank to adjust the cutter to

line up on my pencil marks at each end. Of course this point is best approached

in slow steps roughing out the wood some way from the pencil line first. Having

completed the two sloping sides to the bore, and roughed out its base as shown

on figure 3, the semi-circular cross section was quickly finished off with a

7mm rounded blade chisel. Plenty of sandpaper was used to finish off the bore.

The "lid" was then planed down on both sides to its final thickness of 3 mm and

sandpapered smooth so that is made a good fit with the bore. I then screwed it

onto the bore with countersunk brass screws.

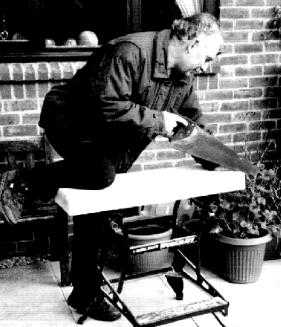

Figure 5: The playing position.

Screwed together, the recorder bore and lid

are much more robust and the outside of the bore can be planed off. I made a

6-sided shape giving a flat bottom which sits nicely on the thumb later.

Deciding how much to plane off is a compromise between strength and weight. I

left a wall-thickness as little as 3 mm on the sides. This gave a total

recorder weight of only 460 grams!

Now is a good time to

sharpen your best 25mm flat chisel, have a cup of tea so that you are fresh and

relaxed, and prepare to cut the fipple from your planed lid. There is room for

an edge 25 mm wide. I defined the angled edges with two sawcuts, cut out the

wedge with the chisel, and severed the sharp end with a blow on my chisel. It

took only 10 minutes.

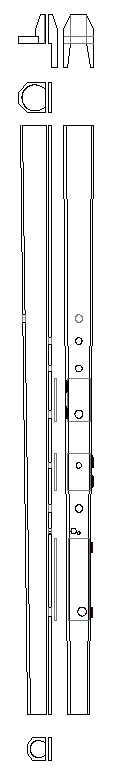

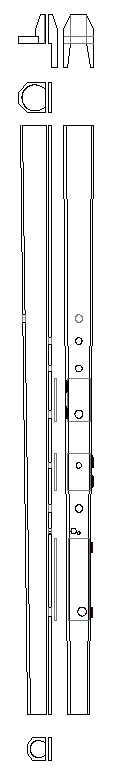

Figure 6: The plan (right) elevation(left) and end sections (top and bottom). At the top

are the mouthpiece plans and elevations

The wind pipe

aperture needs to be about 1 mm deep and 25 mm across to match the fipple, and

at least 15 mm long. I made it from two flat pieces screwed together. The lower

piece contained the entire 1 mm grove so that when you peered through the blowing

aperture you could see the fipple edge nicely framed near the top of the

aperture. A third flat piece covered the fipple end of the recorder. The

windpipe can be widened out to blow directly as in the figure, or you can

make the fipple on the lower surface.

Do not blow into your completed mouthpiece and

bore just yet! It will depress you. The next job is to buy some kitchen sealant,

undo all the screws, and place sealant along all the surfaces that should be airtight.

PVA wood glue would do the job, but the sealant allows the pieces to be

prized apart for the inevitable adjustments. My recorder then sounded a most

melliferous low F! The holes can now all be drilled. It is worth investing in a

proper wood drill with a central spike and giving a clean edge. The placing of

the holes on a flat lid is a bit of a problem. I used the width of the lid to

help the holes fit my fingers. I made the keys out of 3 mm thick flat wood from

the left-over timber. The tiny hinges and screws were difficult to buy in DIY

stores but easy in a little old-fashioned ironmonger in Burnham on Sea! I found

three quality coil springs in an old gramophone turntable. The pads need to be

adjusted so that they sit exactly parallel to the hole apertures beneath them.

For the pad surface, some fine leather proved less good than an old bicycle

inner tube, which in turn was less good than some softer plastic rubbery foam

material. I cannot say that the end result is as good as that of the best round

bass recorders, but in playing you soon get used to the positioning of the fingers.

The playing position in figure 5

shows the fingers on the corners of the two central keys, where they give the

most leaverage. The bottom F key needed an extension piece for my little finger

beneath the surface of the lid.

Figure7: Playing with the Wantage recorder group within a few weeks of starting

construction

Tuning is patience! A

piece of sandpaper wrapped round a pencil will widen the holes gently. I

started at the bottom of the register and moved upwards using my ear and an

electronic organ. £20 will buy an electronic tuner. I varnished and sandpapered

the wood both inside and outside, several times!

After all the thinking and drawing, the construction job took only a few working days.

It seemed much easier than making its wooden case.

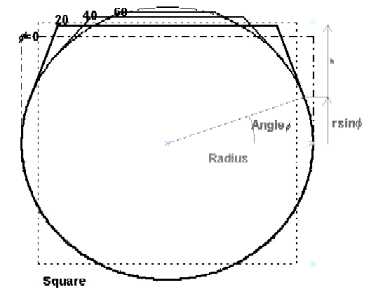

Appendix:

The mathematics between round and square

Exploring figure 1 in more detail, a circular cross-section of radius r

has the area A = p

r2.

A square cross-section with the same area (dashed) has a side-length

w = (p

/2)1/2r.

A semi-circular round base of radius r with a rectangular top section 2r

wide, (dot-dashed) needs to have a height

h = (p

/4)r.

If the circle is extended on each side until it

makes an angle f

with the horizontal,

rsinf

above the circle centre, the upper side walls

make an angle f

with the vertical, and extend for a vertical

height

h = r { cot f

- [ cot2f

+ (f

- p

/2)/sin f

+ cos f

] 1/2 }

h has the value 0.5302 for f

=20 degrees.