Prof. Windsor will review the history of fusion energy and the barriers to its widespread commercial use, and then explain the headline-making developments from late 2020. Before then, physicists said that fusion energy was at least 50 years away (and may never be practical). But now, the estimate is *less than five years*. This could be the planet saving technological development for which we have all been hoping!

This event was proposed by Ahmad Barakat '21 and Tim Bechtel and is sponsored by the Departments of Earth and Environment and Physics and Astronomy.

The talk was

reviewed by Peter Durantine

Click on the arrow to hear the actual webinar

I read that 80% of the UK now think there is a climate emergency. It may have been extinction rebellion, or our own David Attenbrough, or just that we can all feel it. Todays question is "what do we do about it now?" How should we to act to get energy sources that are safe, sustainable, C02-free and base-load? I will argue that we need all the options we can, and fusion is potentially one of the best. So when I was asked 8 years ago, by old colleagues to join Tokamak Energy I immediately said yes. It has a great team, now much larger than the names here. Its focussed on solving the problems of fusion energy. We know its hard but we have a road-map to get us there as soon as we can.

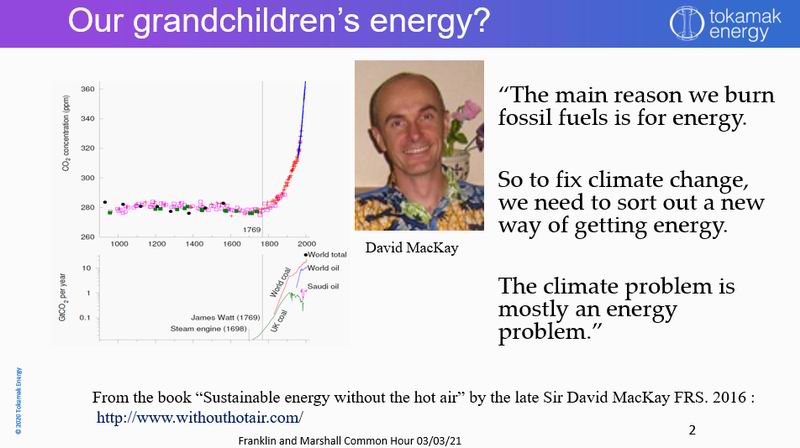

One of my scientific heroes is David MacKay. He came to my life through his Bayesian neutral networks, but then he turned to energy problems. He made a

website which convinced me of the problem. This graph showing C02 level rising with fossil fuel use is completely convincing. He went though the options we have for reducing emissions both personally and collectively. 6 years ago it turned it into the influential book

Sustainable energy without the hot air. Its available free on the web. To quote "To fix climate change, we need to sort out a new way of getting energy."

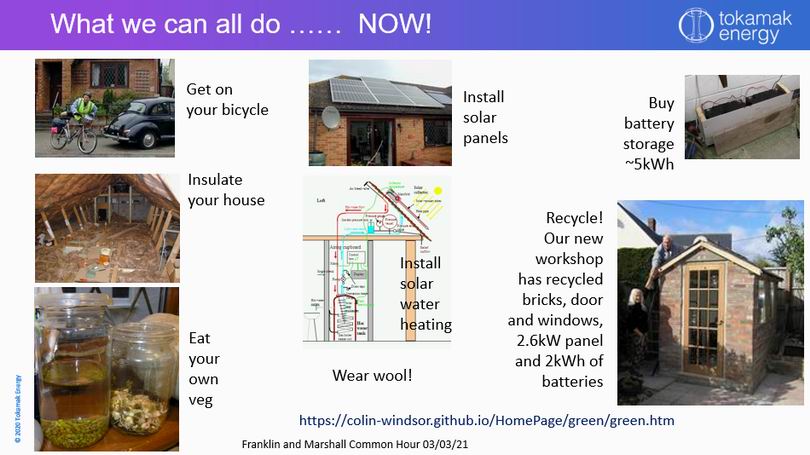

I tried to follow David and so should we all. Now! Today! See my

home page on greening our house

Get on your bike: insulate your house: eat your own vedge, You don't need the rented allotment that we have. Mung beans grow in a few days to gorgeous sprouting beans. Of course install solar PV panels, solar water heating, batteries. Recycle everything! This is our new lockdown workshop which was

build during last sammer's lockdown with my wife Mo. It uses recycled bricks, door and windows. Mo reminded me to "wear wool".

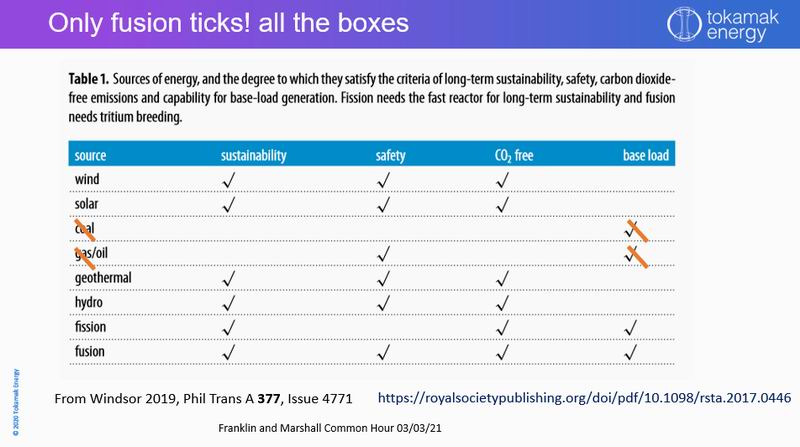

Here are most of the readily available energy sources. This table comes from

the introductory paper for the Royal Society Disscussion meeting in 2019. We want to cut out coal, oil and gas, but lets use all the others. Wind and solar are great and we should be delighted at the contribution they now make. But there can exist months of cloudy, wind-free days, so we need a base-load source.

Of course this table could change. One day there may be batteries for gigawatt months, Hydrogen generation by electrolysis might solve renewables storage: a big superconducting wire following the sun round the equator could solve everything, but not yet.

We are left with fission and fusion for base load options: but only fusion ticks all the boxes.

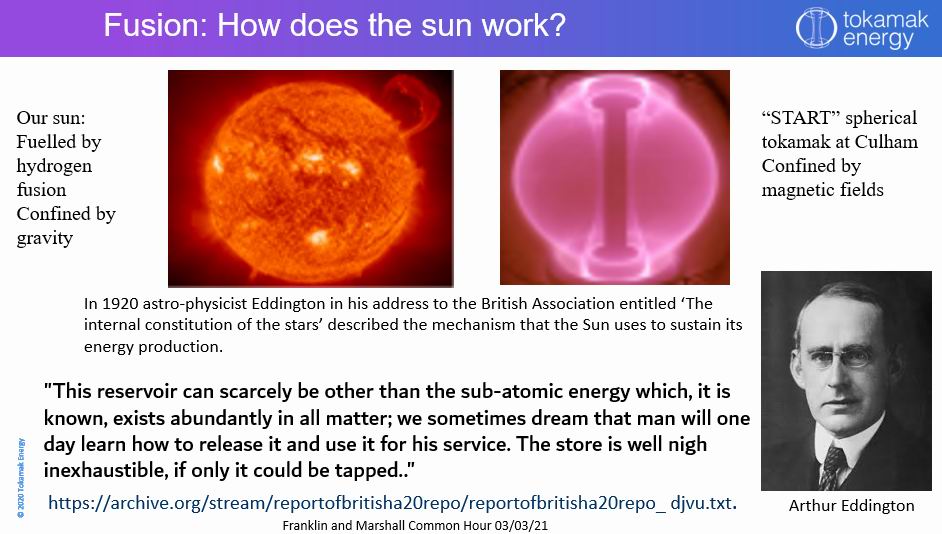

Lets look at fusion. It is amazing that 100 years ago, nobody understood how the sun worked. In 1920 the Cambridge astrophysicist

Arthur Eddington in a talk to the British Association gave us fusion as the answer. Miraculously it is

still there on the web for us to read, "We sometimes dream that man will one day learn how to release it and use it for his service. The store is well nigh inexhaustible, if only it could be tapped"

Eddington's explanation happened because in Cambridge, that same year,

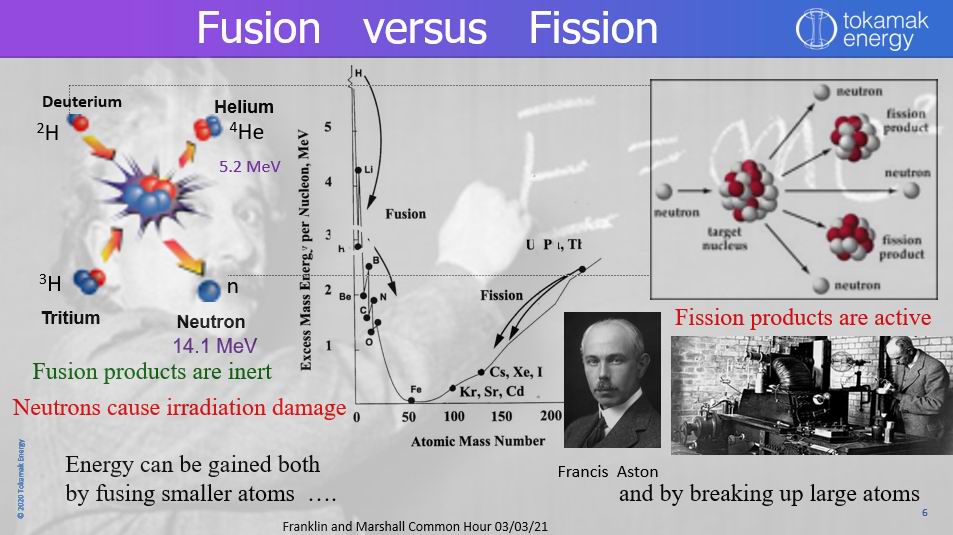

Frances Aston built a mass spectrometer for measuring atomic weights. Chemists will know that atomic weights are close to integers, depending largely on the number of protons and neutrons making up the atom. But not exactly! The curve shows this excess energy for each nuclide plotted against the atomic number. It is seen that there is a broad minimum at around iron with atomic mass 50. This is the reason why 90% of the earth's core is made from iron! There is relative instability at much higher or much lower atomic numbers.

You see in the background another hero, Einstein who while working in the Swiss patent office gave us his famous E=mc2 equation: mass can turn into energy. In fission big atoms break up to give us less mass and so more energy and two rather nasty fission products. In fusion hydrogen isotopes give us stable helium, like you put in balloons, and stable neutrons. The helium stays in the plasma and gives up its energy to carry on the reaction. The neutrons escape to heat up steam for electricity and make more tritium.

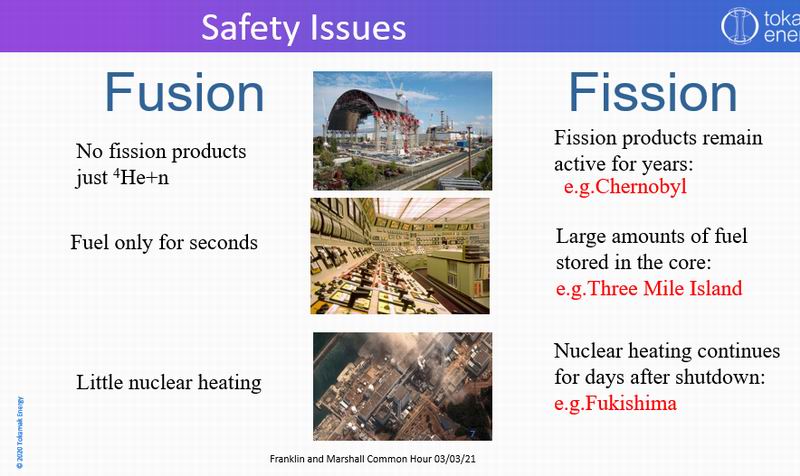

Why is fusion safer than fission. Let me go through these three horrid fission disasters and why they could not happen with fusion.

At Chernobyl a catastrophic criticality released all those radioactive fission products I mentioned. Fusion produces no such products

At Three Mile Island a cooling problem let to fuel melt down. In fusion the fuel is only added second by second as it is needed

At Fukushima, the reactor was shut down OK, but "delayed heating" melted down the core. Fusion has hardly any delayed heating. Fusion is inherently safe.

But its difficult. Here's another hero,

John Lawson who I did meet once. Way back in 1955 he wrote this

most secret report which we can now all read. He showed that three conditions must be met simultaneously to form the famous "triple product"

The density should be large enough for atoms to be likely to collide

The temperature should be large enough to overcome the Coulomb repulsion between the hydrogen isotopes

The energy produced should not be lost too quickly. The time for heat to flow out from the fusion area must not be too long.

As he said at the time, "...even with the most optimistic assumptions, the conditions ... are very severe."

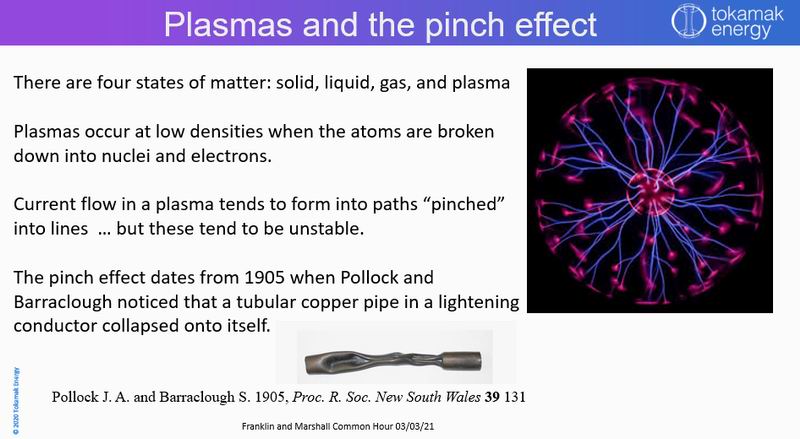

What is a plasma. We all know plasmas from the famous plasma ball. It is the fourth state of matter when the atoms composed of nuclei and electrons are broken apart. Even at low density, they conduct electricity quite well.

The plasma ball shows us two things: Current likes to go through a plasma in a narrow path: almost like a filament. This is the pinch effect.

The current paths are always moving. Plasma instabilities are a fact of life, and have been a perennial problem for fusion power.

How can we use the pinch effect?

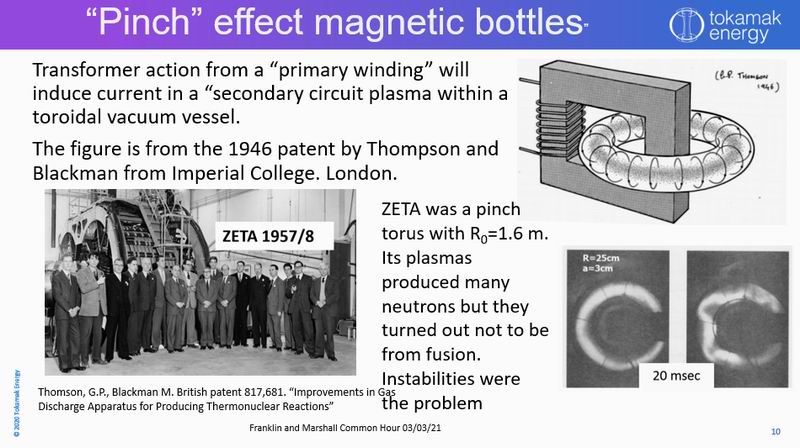

A way to contain a hot plasma is to ensure it has no ends by going round in a torus.

Transformer action can induce a current. The torus is the secondary winding.

The patent for this was from George Thompson in 1946

It lead to ZETA, a quit substantial 1.6 m radius torus, which did manage to make many neutrons but the confinement time was much longer than expected. Instabilities again!

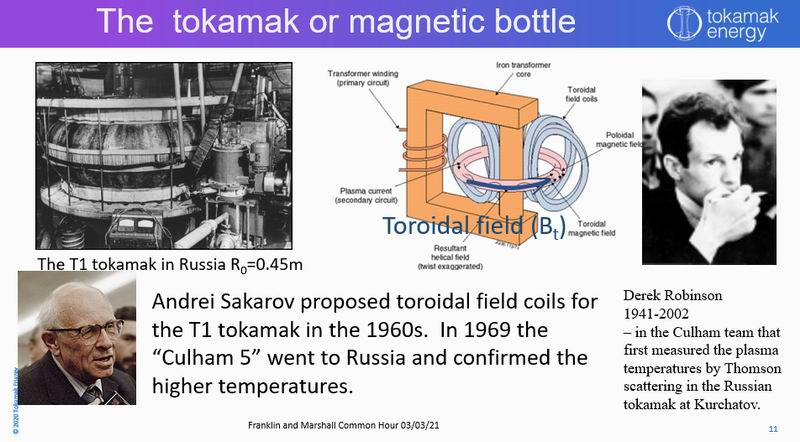

Then there was a breakthrough. Tokamaks were invented following theory by the famous Russian theoretician

Andrei Sakarov in the 1960s.

He proposed using strong magnetic fields along the torus, the toroidal field Bt created by toroidal field coils, in blue in the picture to stabilise the plasma. It worked and I will often mention Bt in this talk. But the high temperatures claimed by the Russians were not believed.

Derek Robinson is another of my heroes. In the middle of the cold war he was in the team from Culham lab used the doppler broadening of scattered light to confirm their claims. Derek learnt Russian, was there all winter, became part of their team and made the visit a success.

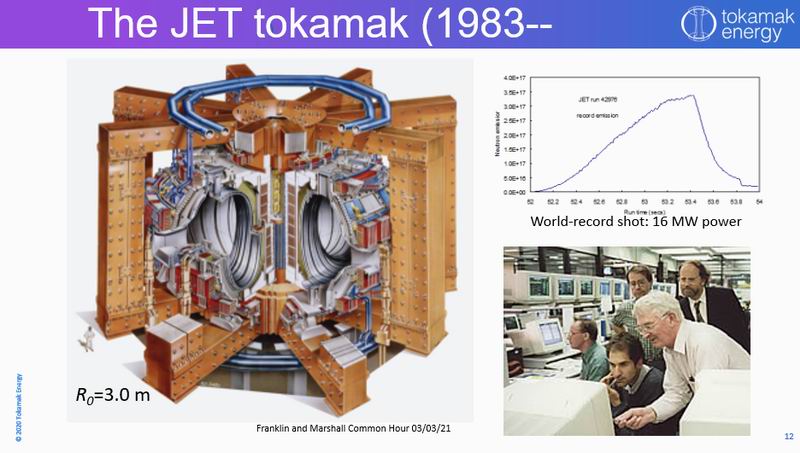

Better and better tokamaks were built, leading to JET, the Joint European Torus with 3 m major radius which showed that fusion worked! Look at the man in the corner.

In 1997 it produced 16 Mega Watts a fusion power, a very considerable amount of fusion energy!

It reached 60% of the "break-even" the target of making more fusion energy than is needed to heat the plasma.

I was lucky enough to be around at that time, as part of the diagnostic team. I still remember the excitement in the control room of those days.

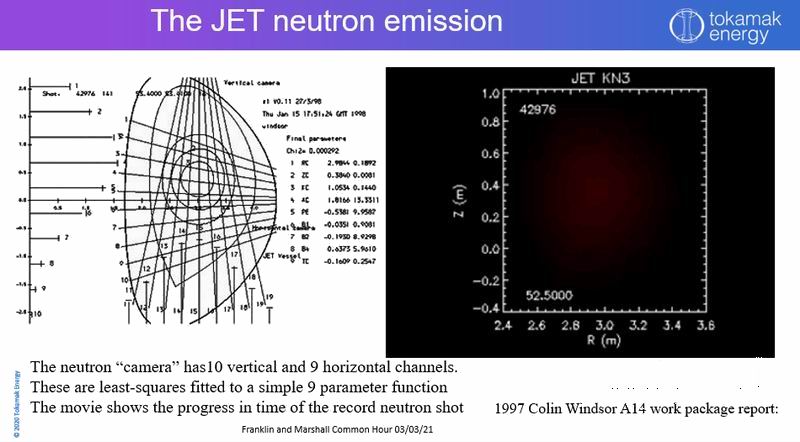

I was in the team running the two neutron cameras that recorded the fusion neutrons along 10 horizontal and 10 vertical paths.

I was able to reconstruct the

profile of the neutron production as in the video.

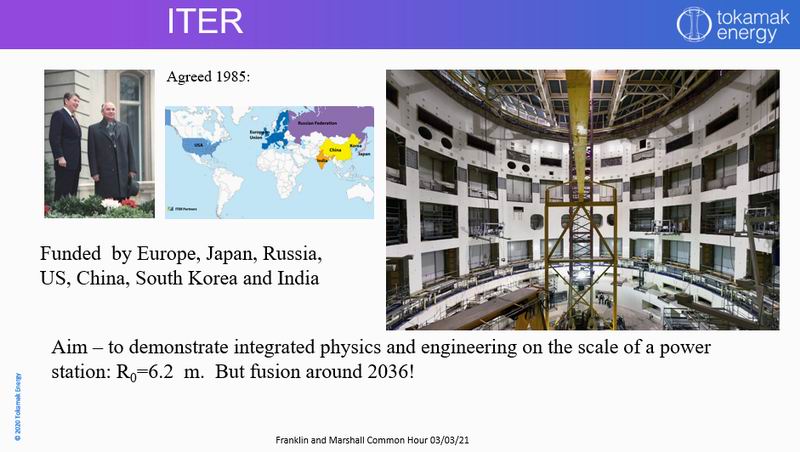

I was not in plasma physics in 1985 but I remember the excitement that I felt when

ITER, the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor as it was called then, brought the whole scientific world together to co-operate in reaching break-even. It was a JET doubled in size to 6.2 m radius with low temperature superconducting magnets. Its big: look at the man.

It is going well and expects a plasma in the next few years and fusion around 2036. I think we all wish it well.

One problem it is that it is the epitome of a "mega-project". ITER is $22B. Projects that big that needs several companies, or countries to complete. They are always difficult to manage for obvious reasons. Statistically they are late and over budget.

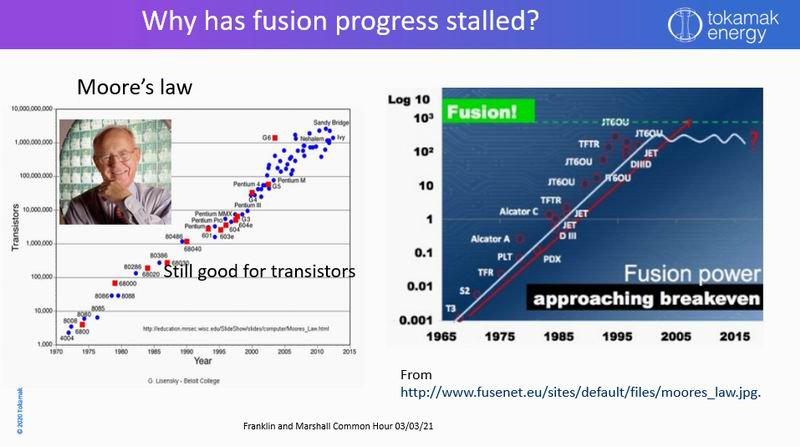

We are all familiar with Moore's Law which showed the power of computers doubling every couple of years. It still carries on.

With fusion tokamaks it followed a very similar path for 30 years up to JET, but then it stopped. This old slide appeared on the internet in 2015 and we are 7 years on! There has been no fusion power record since 1997.

We are all waiting for ITER! At my age I cannot wait that long.

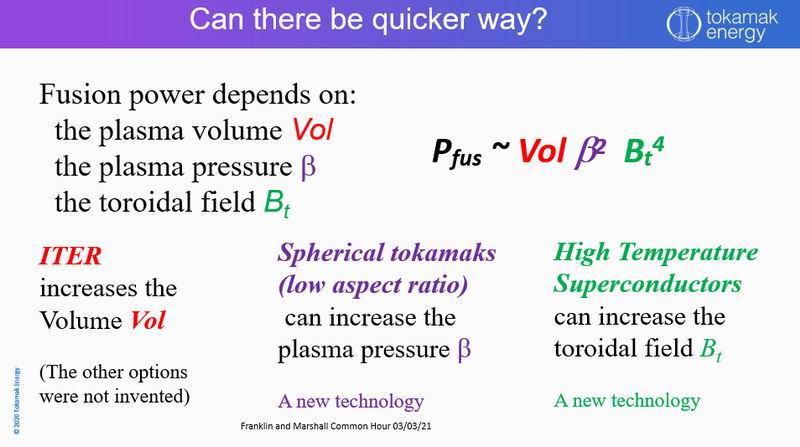

Can there be a quicker way? Fusion power depends on three factors,

Volume: this was the ITER way:

Normalised plasma pressure beta: spherical tokamaks can dramatically increase it.

Toroidal magnetic field: Low temperature conductors gave the ITER limit, but then came High Temperature Superconductors which can again dramatically increase it.

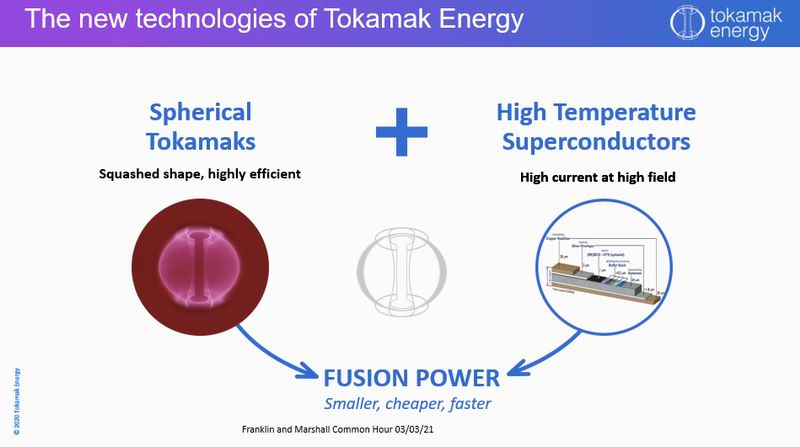

Tokamak Energy has the simple aim of using the two technologies of spherical tokamaks and HTS magnets to make fusion power smaller, cheaper, faster.

Let me discuss these two technologies.

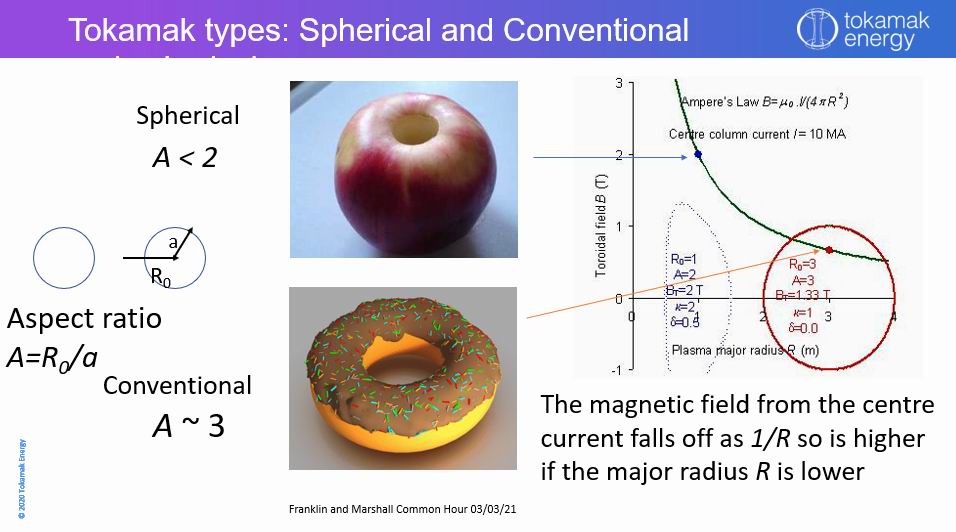

The field in a tokamak mainly comes from the current down its centre rod: down the hole in doughnut or apple

The field from a wire decays as 1/R, so the closer the plasma is to the wire the higher the field: and the higher the beta.

Its as simple as that!

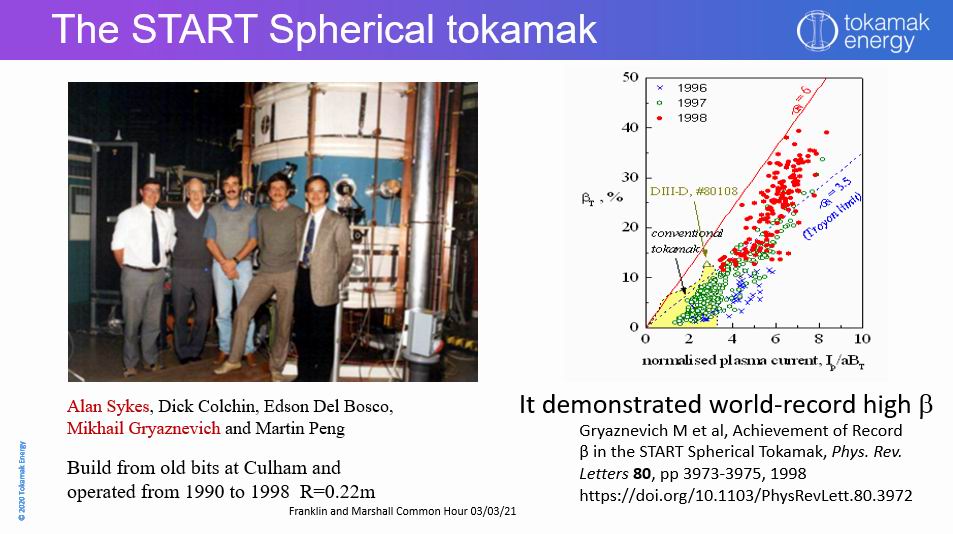

World record plasma densities were achieved by the START team at Culham in the 1990s

The yellow area shows the best betas from conventional tokamaks, the red the new results

It was built from old bits and pieces at Culham, and got started without ever being a formal project

This team deserve to be heroes. Alan Sykes and Mikhail Gryaznevich were the founders of Tokamak Energy: but hero Derek Robinson, now the Culham boss, was right behind it.

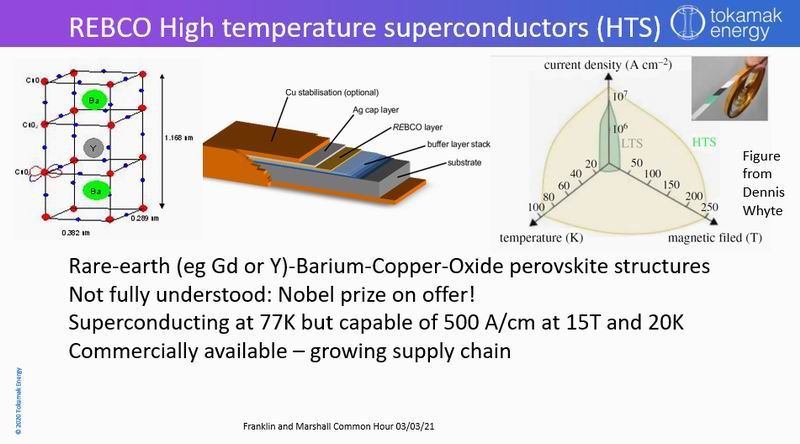

High Temperature Superconductors HTS are a game-changer! LTS and HTS have about the same large current density, but HTS have much larger operating temperatures, and much larger operating magnetic fields.

They are not easy to understand. A Nobel prize awaits someone who can explain them. They mostly have this perovskite structure shown.

The actual cables are about 1cm wide and less than a mm thick and cost around $1 a cm. They are mostly copper for stabilisation: the actual HTS layer is only a few microns thick

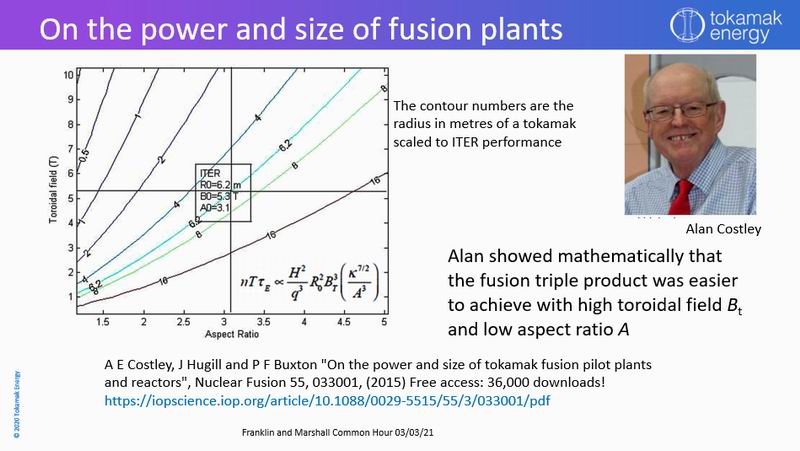

My colleague Alan Costley at Tokamak Energy is another hero. He wrote this

free access paper that as been downloadedmore times than any other paper in Nuclear Fusion.

He explained how for a given set of breakeven conditions, like the ITER ones in the centre of this plot, the radius of the tokamak, given by the numbers on the lines, will go down either by decreasing the aspect ratio (spherical tokamaks) or by increasing the field (HTS magnet)

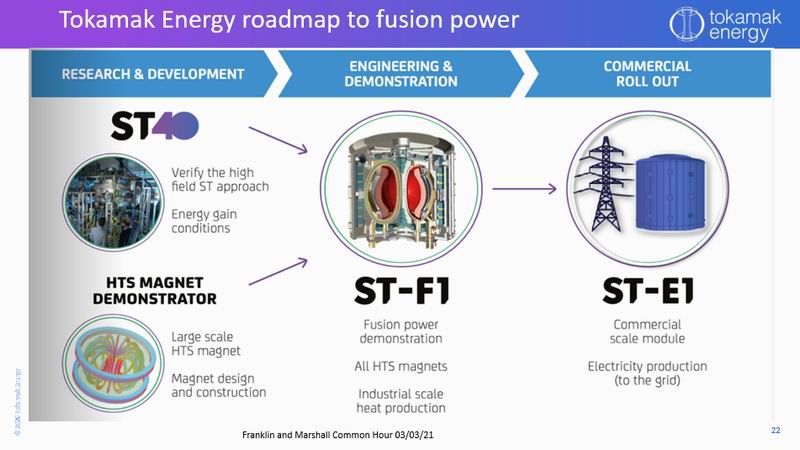

So here is our roadmap to fusion power. We are building the ST40 to understand high field spherical tokamaks.

We are building a magnet demonstrator to understand HTS tokamaks.

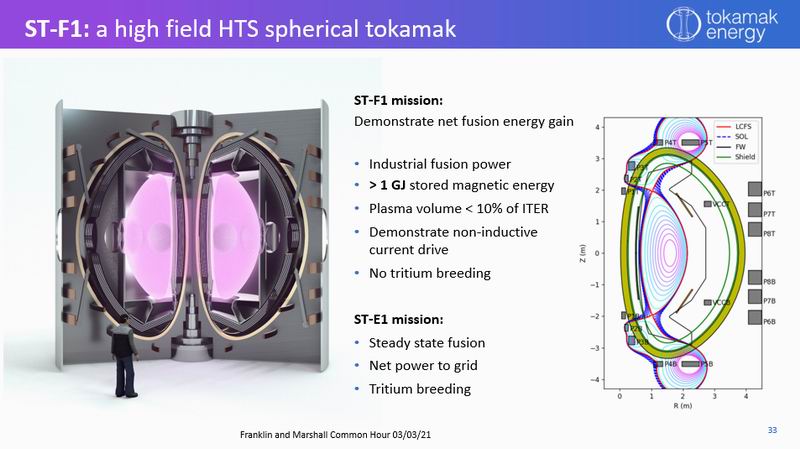

Then comes STF1: a demonstration of fusion power with more energy out than in. It will produce some crucial numbers on "burning" plasmas

The next step is STE1 our prototype power plant "as small as possible for many of a kind production"

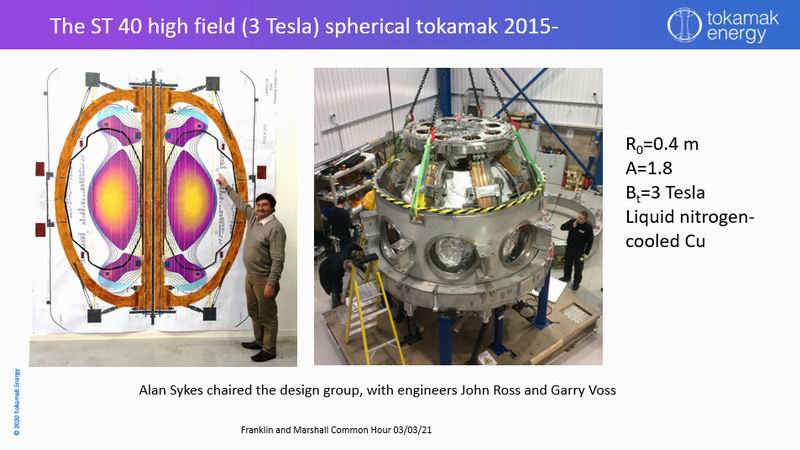

Here's Alan Sykes again: long Scientific Director of Tokamak Energy, who you saw on the START slide.

He chaired the little group with clever engineers John Ross and Garry Voss, and me too, who designed a spherical tokamak with the world’s highest toroidal field, Bt=3 Tesla, achieved by liquid nitrogen cooled copper coils. The design was written in a

Nuclear Fusion paper.

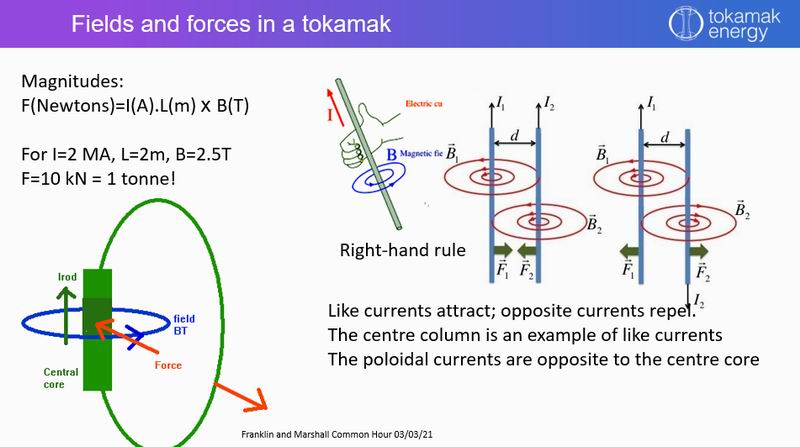

It was not easy to design. Lets do some engineering!

If you have a plasma with a current of 2 MA, sitting in a field of 2.5T, 2m long it has a force of 1 tonne!

If you try and make toroidal coils, like the green line, the like current in the core attract eachother, and the outer return limbs of the tokamak are repelled

Here is my little

demo to illustrated the forces in a highly elongated tokamak. Come and see my new workshop.

The demo sits on the top of the solar-freezer. The positive of the battery is connected to the central red wires, representing the inner central rod of the tokamak. These wires are connected at the bottom to the blue wires which will create the desired toroidal field around the central column.

When I connect the current, the red central wires show the "pinch" effect and come together and the blue wires are forced outwards.

Just as in a real tokamak, the situation can only last a short while before the coils get too hot!

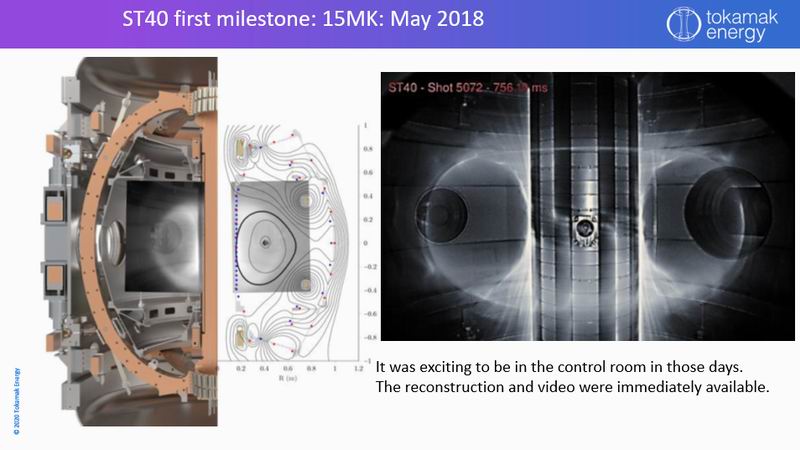

Here is ST40 in operation two years ago meeting its milestone of 15 million degrees. You can see all the engineering necessary to keep those forces under control. It can only operate for a second or so, before the copper heats up to much, and the current from super-capacitors runs out too.

I was lucky enough to be asked to be part of the team with the objective of trying to find the optimum conditions.

The analysis of the plasma into field lines and the plasma boundary are immediately available after the shot.

Immediately after meeting the milestone we move into this lovely spacious building, and the team grew in size with the building.

Its now around 100 strong and we are still hiring all sorts of people.

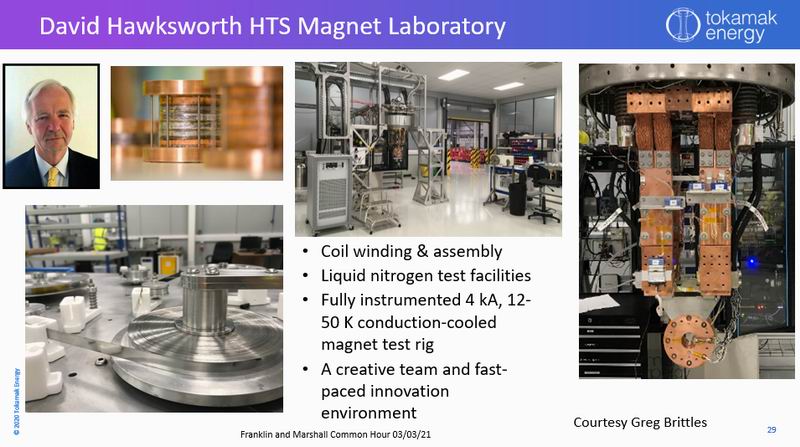

At the same time as spherical tokamak technology is being developed, so in an adjacent area high temperature superconducting magnets are being developed. David Hawksworth who died recently developed MRI magnets and was one most influential consultants. So have our own coil winding and cold test facilities, but most importantly a really good team

Greg is a great team leader. You can all watch this video on Youtube. But I want to talk about the problem of quenching.

A high field magnet carries a lot of energy, if there is a defect which reduces the superconductivity slightly the material may go normal. With an insulated conductor the current has nowhere to go and so heats up quickly. This can spread to nearby superconductors and so the magnet quenches and could be destroyed.

If there is no insulation between the coils, the problem is avoided as the current is taken by other strands but the coils then take a long time to energise. Is there is middle way with the "right" resistance.

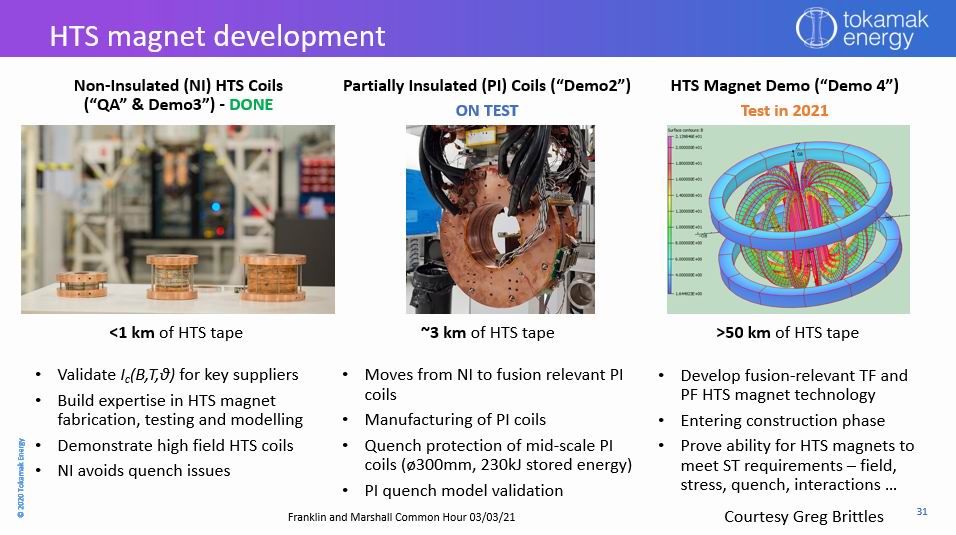

Demo 3 with non-insulated magnets was shown to work exactly as expected.

Demo 2 with partially insulated coils is now on test and working as expected. They are indeed amazingly stable and resistant to damage of many sorts.

Demo 4 a proper tokamak configuration at 0.4 m radius is due this year.

How do you design a tokamak that will get to fusion conditions and measure the numbers like confinement times that we need to build a fusion power plant?

This is old

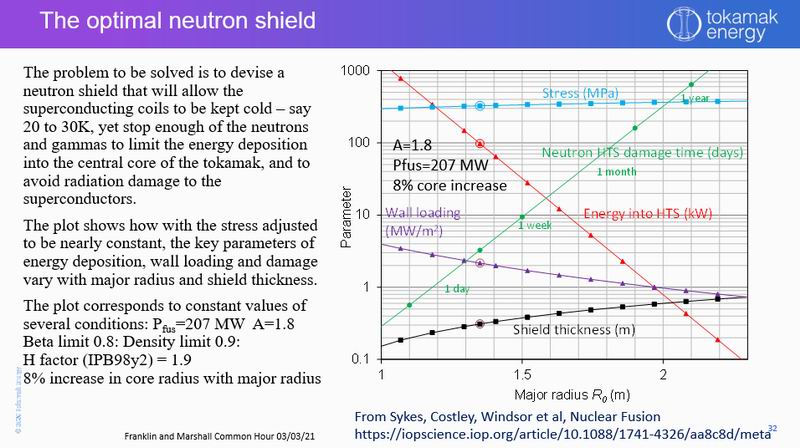

published work, but it shows the results from "system codes" which calculate all the reasonable parameters of a tokamak of given radius and power. It assumes known limitiations such

as the "beta limit", "density limit" and "Safety factor".

In particular this series is designed to be at the limiting stress given by the blue line at the top.

Also crucial Is the "wall loading" which is very high, and the energy deposition into the HTS the red curve which goes steeply down with major radius.

Also a limiting factor is the radiation damage to the HTS coils caused by the neutron flux, and the curve shows the number of days it could last.

The conclusion is that it is reasonabele for a tokamak of this kind to work!

So where are we heading for. These are the two crucial next steps

STF1 will demonstrate spherical tokamak plasma physics for long enough (5 secs) to give us the crucial confinement times

Big enough so that physics risk is low and the hardware can handle the fusion power ~5 years from now

ST-E1 for sustained power ~200 MW for years, with electricity output and tritium breeding

First of a kind of say group of 10 identical STE1 which can guarantee load factor, and maintenance outage.

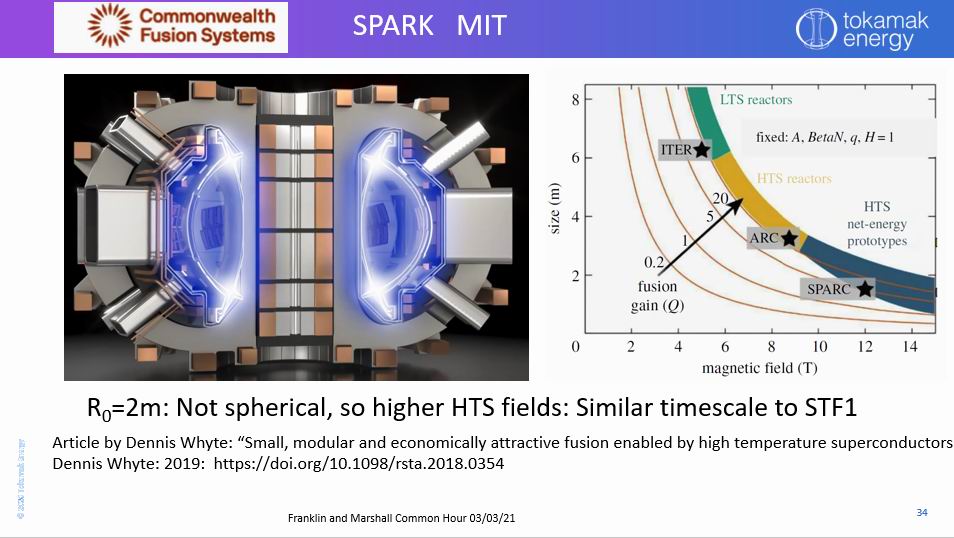

So I must mention our US opposition from MIT. Back in 2015 Dennis Whyte and Zac Hardwick came over and we talked over all our common problems.

Their's is not an easy design as the non-spherical tokamak means higher fields are necessary for a given

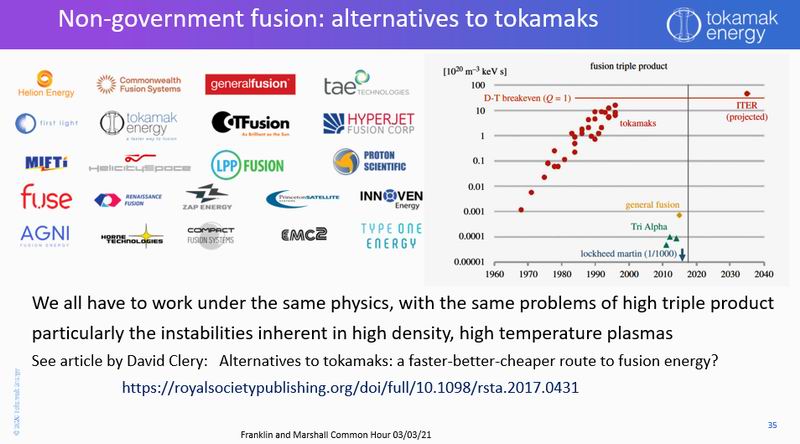

Some of the other private approaches to fusion are listed here. Only Tokamak Energy and Commonwealth fusion are tokamaks, the rest are trying completely snew approaches. For details can I refer you to David Clery's paper: he has made a special study of these. The curve shows the triple product for tokamaks compared with some alternative projects. They are all well down in this race, but that could quickly change.

A problem is that whatever the method of getting there the physics is always the same. The Rayleigh Taylor instabilities are universally present and spoil the confined plasmas we are all trying to make.

The roadmap I showed is just a highly simplified version for publication. The real one is a very large spreadsheet. I have just spent a couple of mornings of zoom meetings looking at the "known problems" we have in our shielding field and how and when and for how much we plan to address them. Its not so easy to address the "unknown unknowns".

For further reading can I recommend the published in the world's oldest journal Phil Trans A

proceedings of this meeting

and My introductory paper

Can I repeat that jobs can always be found at

www.tokamakenergy.co.uk

To join our talent pool simply send your CV, clearly indicating what position or area you are interested in work in to: careers@tokamakenergy.co.uk

Copyright 2021: Colin Windsor: Last updated 06/3/2021