The energy supply to heat the homes of our grandchildren

remains uncertain. The options available to us have been

detailed by David Mackay in his readable book Sustainable

Energy, Without the Hot Air [1]. Mackay describes how at present

we use around 125KWh per day per person, produced largely

by CO2-emitting coal, oil and gas. There is now no doubt that

climate change is with us. As David King, our Chief Scientist from

2000 to 2007, said: "Climate change is the most severe problem

that we are facing today, more serious even than the threat of

terrorism." We have to change our ways. There is solar and wind

energy, but the sun does not always shine nor the wind always

blow. There is nuclear fission energy, which the UK pioneered

and which has served us well, but it is not without risk and its

public acceptance is fragile. Fusion is one remaining option for a

sustainable, safe, CO2-free, base-load energy source (Figure 1).

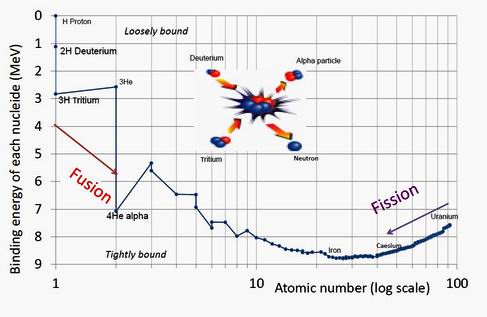

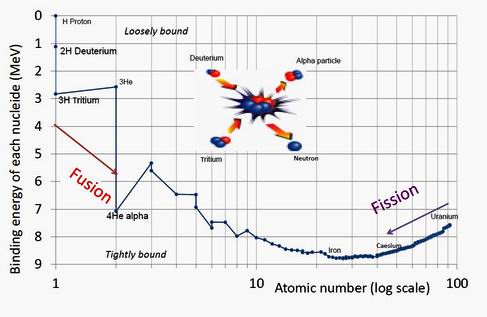

Figure 1: Nuclear power from fusion and fission. The graph

shows the excess energy of different nuclei plotted against

atomic mass. The very light atoms have a high excess energy

and can become more stable by fusing together to produce

larger nuclei. Heavy nuclei can become more stable by splitting

up to produce fission products of intermediate mass.

Figure 1: Nuclear power from fusion and fission. The graph

shows the excess energy of different nuclei plotted against

atomic mass. The very light atoms have a high excess energy

and can become more stable by fusing together to produce

larger nuclei. Heavy nuclei can become more stable by splitting

up to produce fission products of intermediate mass.

The fusion reaction

Nuclear fusion is the reaction that powers our Sun. The fuel is

hydrogen nuclei, protons, deuterons (D) and tritons (T). In the

heat and gravitational 'bottle' of the Sun, these can be forced to

overcome their electrostatic repulsion and join together to form

the stable helium nucleus - or alpha particle - and a neutron

(n), together with a great deal of energy: 14MeV flies off in the

neutron, which may be used to heat up a water jacket to make

electricity; the charged alpha particle, with 3.6 MeV of energy,

remains in the plasma, giving up its energy and helping to sustain

the following reaction.

2D+3T = 4He+n +17.6MeV

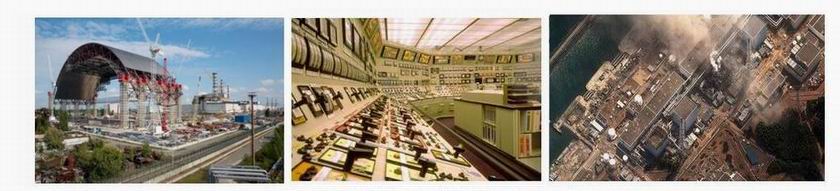

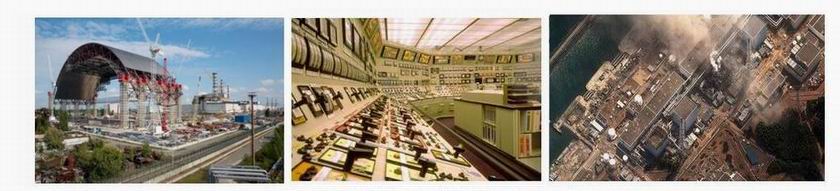

There are important differences in the safety issues for nuclear

fission and fusion (Figure 2). At Chernobyl, the criticality accident

only occurred because a fission reactor contains large reserves

of fuel. In a fusion reactor the hydrogen fuel is continuously

injected into the plasma so that it can only sustain fusion for

seconds, and a 'criticality' accident is impossible. At Fukishima

the reactor was properly shut down, but the meltdown occurred

because spent fuel continues to produce heat, which could not

be removed because of the flooded back-up generators. There is

no such 'delayed' heat in a fusion reactor. At Three Mile Island,

human error caused the meltdown but the problem was the high

reactivity of the long-lived fission products that were allowed to

escape. The fusion products are the benign helium and neutrons.

The neutrons produce some activation in the structural materials,

but with the correct choice of alloy materials this is a minor

issue compared with the fission spent fuel which has proved so

expensive to deal with.

Figure 2: The three accidents that changed public acceptance of fission power. In a fusion reactor there is no possibility of the

'criticality' at Chernobyl (a), the release of highly active 'fission products' at Three Mile Island (b), or the 'delayed heat' at Fukashima (c)

Figure 2: The three accidents that changed public acceptance of fission power. In a fusion reactor there is no possibility of the

'criticality' at Chernobyl (a), the release of highly active 'fission products' at Three Mile Island (b), or the 'delayed heat' at Fukashima (c)

In defence of fission it must be said that the public mind tends

to over-estimate the actual deaths and premature deaths (56

and 4000 respectively from Chernobyl according to Wikipedia),

compared with, say, the seven million premature deaths per year

estimated by the World Health Organisation to result from air

pollution [2].

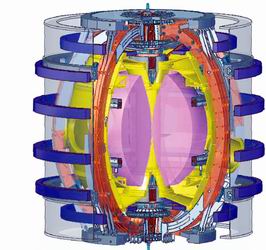

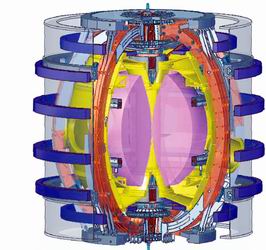

Figure 3: The ST40 tokamak. The plasma (violet) is the elongated

toroid. The white coils produce the toroidal field along the

direction of the plasma which helps to stabilise it. The blue coils

produce the vertical fields that shape and help form the plasma.

Wound around the brown central column is a solenoid that also

helps drive the plasma current.

Figure 3: The ST40 tokamak. The plasma (violet) is the elongated

toroid. The white coils produce the toroidal field along the

direction of the plasma which helps to stabilise it. The blue coils

produce the vertical fields that shape and help form the plasma.

Wound around the brown central column is a solenoid that also

helps drive the plasma current.

The tokamak magnetic bottle

In order to make the fusion reaction work on Earth, the

gravitational confinement operating in the Sun must be

reproduced in some way. The tokamak (Russian for magnetic

bottle) provides a magnetic confinement that is able to hold the

high-temperature plasma away from all walls. Figure 3 shows the

typical tokamak design, specifically the ST40 spherical tokamak

being built at Tokamak Energy. (Conventional tokamaks have a

wider, ring-doughnut shape but similar configuration.) It has a

toroidal vacuum chamber containing the plasma, and toroidal

coils which produce a strong field parallel to the plasma direction.

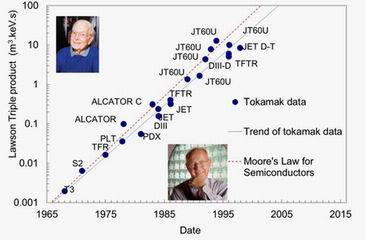

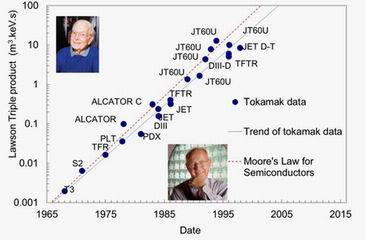

Figure 4:The historical increase in the fusion Lawson 'triple

product'. For three decades until 1997 the fusion triple

product increased exponentially (points and blue line) with

around a two-year doubling time, almost the same as the

Moores's law for semiconductors (red dashed line). Only the

JET and TFTR data points used tritium fuel, the other points

are extrapolations from deuterium plasmas.

Figure 4:The historical increase in the fusion Lawson 'triple

product'. For three decades until 1997 the fusion triple

product increased exponentially (points and blue line) with

around a two-year doubling time, almost the same as the

Moores's law for semiconductors (red dashed line). Only the

JET and TFTR data points used tritium fuel, the other points

are extrapolations from deuterium plasmas.

Since the earliest ZETA days a key problem of plasma physics has

been the stability of the plasma. Any contained plasma must be

'pinched in' away from the container walls; however, the plasma

column wiggles about and tends not to be stable. In a tokamak

the toroidal coils form a strong magnetic field along the plasma

path, which tends to improve its stability.

How can progress towards fusion be measured? One answer

was given by John Lawson in 1955 who, while working at

Culham, devised the 'Lawson triple-product':

nTtE > 221 m-3keVs

where n is the plasma density, T is the plasma temperature in keV,

and tE

is the plasma 'energy confinement time', i.e. the mean

time for energy to diffuse away from the plasma.

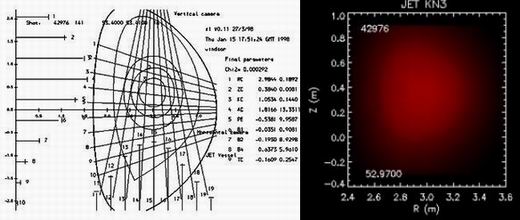

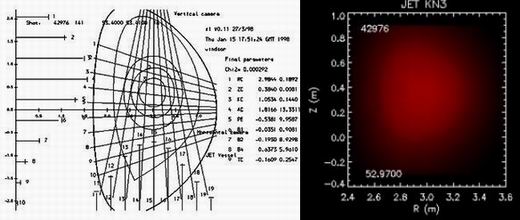

Figure 4 shows the increase in fusion triple product from

the first T3 tokamak in Russia to the JET tritium runs in 1997.

A doubling time of around two years was achieved largely by

building ever-larger tokamaks. The JET tokamak has a major

radius of three metres and achieved some 16MW of fusion power.

Those were exciting days! Figure 5 shows the neutron emission

profile as modelled from the nine vertical and ten horizontal

neutron counters measuring the neutron emission profile along

the lines shown [3].

Figure 5:The recordbreaking shot 42976 on JET. On the right is

a reconstruction of the neutron emission as measured by the vertical

and horizontal neutron cameras [3].

Figure 5:The recordbreaking shot 42976 on JET. On the right is

a reconstruction of the neutron emission as measured by the vertical

and horizontal neutron cameras [3].

What can the physics say?

The increasing triple product curve stops at 1997, as the whole

world looks forward to the ITER project with its 6.2 metre major

radius. Its centre column alone weighs more than the Eiffel tower.

The project is funded by Europe, Japan, Russia, USA, China,

South Korea and India, and we all eagerly await its answers to the

unknown conditions of a burning plasma. But ITER has already

shown us that building bigger has its own problems. Can there

be quicker way by building more compactly, to produce smaller

power plants better suited to the energy market? The physics tells

us of options that were not available in the 1990s when ITER was

designed. The fusion power (Pfus) can be written as

Pfus ~ b2BT4V

where b

is the plasma pressure, Bt is the toroidal field

and V is the volume. The

ITER design had the conventional JET shape, largely defining

the plasma pressure, and used the best low-temperature

superconducting magnets available to give the highest possible

toroidal field. Increasing the volume was the only option available

then.

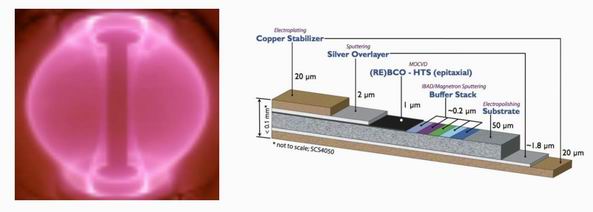

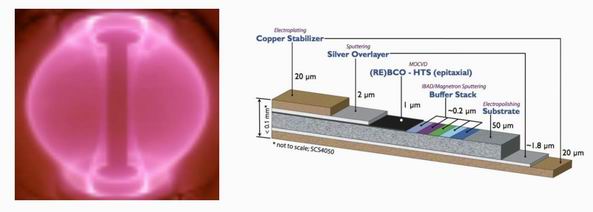

Figure 6: Two developments from the 1990s: (left) the START spherical tokamak; (right) the high-temperature

superconducting 'REBCO' tape.

Figure 6: Two developments from the 1990s: (left) the START spherical tokamak; (right) the high-temperature

superconducting 'REBCO' tape.

There were two developments in the 1990s which changed

this. First, the START spherical tokamak at Culham, shown on the

left of Figure 6, demonstrated that making the plasma the shape

of a cored apple rather than a doughnut could give a higher

plasma pressure. Secondly, the discovery of 'high-temperature'

superconducting materials showed that the magnetic fields on

the plasma could be much higher than previously thought. The

right of Figure 6 shows the cross-section of the high-temperature

superconducting tape. Most of the tape is copper stabiliser and

substrate. The superconducting layer is only one micron thick.

Figure 7: The Tokamak Energy team at Milton Park.

Figure 7: The Tokamak Energy team at Milton Park.

TokamakEnergy.co.uk

Tokamak Energy was founded by the START pioneers Alan Sykes

and Mikhail Gryaznevich, with David Kingham as chief executive

officer. With just a small number of UK investors who actively

guide the company, and the relatively tiny number of staff shown

in Figure 7, it has been able to forge an alternative path to fusion

energy based on rapid development using small prototypes. At

their premises in Milton Park in Oxfordshire a small test tokamak,

ST25, has been built to investigate innovative solutions to the key

problems of novel controllable power supplies, plasma start-up

and efficient plasma current drive.

A key challenge in the development of compact fusion is how

to make reliable, high-field high-temperature superconducting

(HTS) magnets. Their operation is quite different from conventional

low-temperature superconductors. They can operate at 77K liquid

nitrogen temperatures rather than 4K helium temperatures, but

much higher fields can be generated if they are cooled to about

20K with helium, hydrogen or neon coolants. At present they are

not available in the kilometre lengths required for a power plant.

New methods for joining them have recently been developed in

house: they involve using hair straighteners, which have exactly

the right temperature-controlled flat surfaces to bond the tapes

nicely together. The quench properties of the HTSs are also quite

different: they seem less prone to the catastrophic quench events

that can occur with conventional superconductors. To test these

technologies, the ST25HTS tokamak has been built at Milton Park.

During July 2015, during the Royal Society Summer Exhibition, it

was run successfully at Milton Park for over 24 hours, as shown in

Figure 8.

Figure 8: Our small tokamak with hight-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets, ST25HTS,

hold a plasma for 29 hours, demonstrating the feasibility of HTS for tokamaks.

Figure 8: Our small tokamak with hight-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets, ST25HTS,

hold a plasma for 29 hours, demonstrating the feasibility of HTS for tokamaks.

A key objective of Tokamak Energy is to design a pilot plant that

would be small enough to manufacture as the first of a series of

units that could be developed incrementally, and linked together

to form a modular power station. This would provide continuity

of supply, economy of mass production and other practical

advantages. The key requirement is that each module should

produce a high gain Qfus in fusion power, where Qfus = power

released/power in.

But how small could the base module be? What are the limiting

factors? What can theory say? What experimental measurements

need to be done?

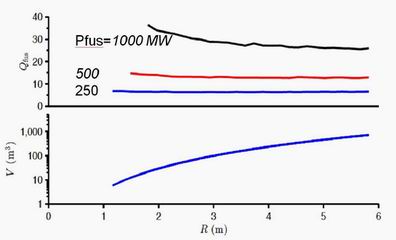

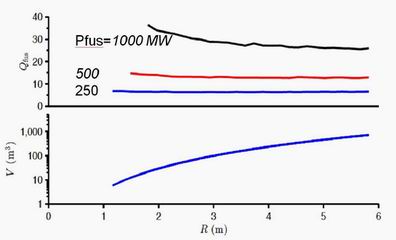

Figure 9: The figure from the paper by Costley et al. [4]

showing that the fusion gain Qfus is only weakly dependent on

device size R but does depend on the fusion power.

Figure 9: The figure from the paper by Costley et al. [4]

showing that the fusion gain Qfus is only weakly dependent on

device size R but does depend on the fusion power.

A theoretical study by Alan Costley and colleagues [4] showed

that when the plasma was operated in a steady state within

reasonable fractions, say 0.8 of the Greenwald density limit and

0.9 of the Troyon beta limit, then the fusion energy gain (and

triple product) depends mainly on the absolute level of the fusion

power and the energy confinement, and only weakly on the device

size, as shown in Figure 9. Further, they showed that the scaling

law used to design ITER needs to be updated. In particular, a betaindependent

scaling is needed to account for recent experiments.

This approach suggests that there is no problem with the

physics of smaller tokamaks. But what about their engineering?

It has long been realised that the slender centre column of the

spherical tokamak is a problem. If made of superconductors they

must be surrounded by a neutron shield, both to reduce the heat

deposition and to reduce radiation damage. If made, instead, of

copper, the ohmic heating is large. Either much energy must be

wasted cooling the centre column, or its temperature must be

allowed to rise during the experiment. This last solution is the one

chosen for ST40, a larger machine under construction by Tokamak

Energy. It is designed to be the world's highest field spherical

tokamak and to establish the physical properties of these plasmas.

ST40 will operate in hydrogen, and will not produce neutrons.

The copper resistivity is lowered by cooling to liquid nitrogen

temperatures, and a window of operation time several seconds

long is available as the centre column heats up from, say, 77K to

200K. Of course there follows several minutes of cooling down

before the next shot.

Figure 10: On the left is a section through the centre column of a

pilot plant tokamak with a tie-rod (green) in the centre then a high temperature

superconductor alloy (purple), a thermal gap (white) and layers of shield material

(blue) and water-cooling (yellow). On the right is the heat deposition as a function of the thickness of the water-cooling

layer.

Figure 10: On the left is a section through the centre column of a

pilot plant tokamak with a tie-rod (green) in the centre then a high temperature

superconductor alloy (purple), a thermal gap (white) and layers of shield material

(blue) and water-cooling (yellow). On the right is the heat deposition as a function of the thickness of the water-cooling

layer.

For a power plant, there are many high-energy neutrons

produced and this option is not possible. An efficient neutron

shield must be designed. This is not easy. The 14MeV fission

neutrons hitting its outer surface create cascades of high-energy

gamma rays which need heavy elements to attenuate them. The

fast neutrons bounce off these heavy elements and need light

elements to slow them down and give up their energy. The Monte

Carlo computations [5] have now been extended and it seems that

the energy deposition could become a manageable 36kW or so

using the shield comprising layers of tungsten carbide separated

by cooling water, illustrated in Figure 10. The graph shows that

the heat deposition increases if the water-cooling thickness is too

small, leading to poor moderation. If the water-cooling thickness is

too large there is insufficient gamma shielding. Better performance

is given when the water thickness close to the core is thicker

than that close to the plasma. Still better performance occurs if

the layer of tungsten carbide closest to the core is replaced by

tungsten boride, which can absorb the slower neutrons.

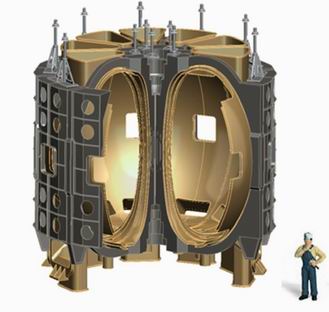

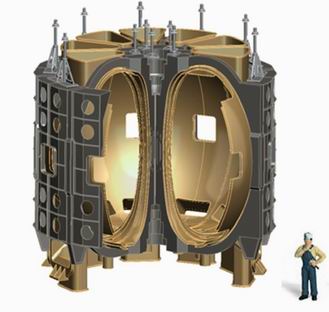

Towards a modular power plant

The power plant modelling by Costley et al. [4] suggested that a

possible optimum size would be with a major radius of 1.35m.

The 36kW of nuclear heating to the superconducting core could

be removed by a cryoplant of around 2MW, which is not an

unreasonable fraction of the 175MW fusion power. Such a pilot

plant is illustrated in Figure 11, which shows a design developed

in collaboration with Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, USA. It

is large enough to be attractive as a unit to a utility company, and

small and cheap enough to be constructed conventionally using

available finance.

Figure 11: A possible modular fusion power plant designed

in collaboration with the Princeton Plasma Physics Institute in

the USA.

Figure 11: A possible modular fusion power plant designed

in collaboration with the Princeton Plasma Physics Institute in

the USA.

Tokamak Energy is breaking the problem of fusion down into

a series of engineering challenges. Our ST40 experiment will give

us the numbers, in particular the energy confinement time in

high-field spherical tokamaks, to design the plant without large

extrapolations. At present the HTS superconductors are expensive

but the technology is developing and their price coming down.

A big market will aid this development. Heat deposition and

stresses in the centre column remain a problem, but new materials

combining the advantages of shielding, strength and toughness

are being developed to cope with them. None of these problems

appear insuperable and fusion in small spherical tokamaks could

be possible quite soon.

References

1. MacKay, D. Sustainable energy, without the hot air www.

withouthotair.com

2. World Health Organisation (2014) New release, Geneva, 25

March 2014 www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2014/

air-pollution/en/

3. Windsor, C.G. (1998) Validated neutron data for physics

studies and their use in tomographic reconstructions from

JET's DTE1 campaign. JET workpackage A14.2d report, F/PL/

WPA14.2d/CGW/1 March 1998

4. Costley, A.E., Hugill, J. and Buxton, P.F. (2015) On the power

and size of tokamak fusion pilot plants and reactors. Nucl.

Fusion 55, 033001

5. Windsor, C.G., Morgan, J.G. and Buxton, P.F. (2015) Heat

deposition into the superconducting centre column of a

spherical tokamak fusion plant. Nucl. Fusion 55, 023014

About the authors

Colin Windsor

Colin Windsor joined Tokamak Energy in 2013 after a career at Harwell working on materials

using neutrons. He came to Culham in 1994 to work on control of the COMPASS-D tokamak

and on the JET tritium campaign. He now works on the neutronics of high temperature

superconductor tokamaks.

Melanie Windridge

Melanie Windridge is a physicist, speaker, writer and communications consultant

to Tokamak Energy. Her PhD focused on vertical stability on the MAST tokamak at

Culham Centre for Fusion Energy. She has published an introductory book on fusion

called "Star Chambers" and a narrative science book called "Aurora".

Alan Sykes

Alan Sykes is one of the founders of Tokamak Energy and a pioneer of the

spherical tokamak concept.

He had a fruitful career in fusion energy at Culham Laboratory from 1965 to

2008 spanning theory and experiment and leading on the record-breaking START

machine.

Figure 1: Nuclear power from fusion and fission. The graph

shows the excess energy of different nuclei plotted against

atomic mass. The very light atoms have a high excess energy

and can become more stable by fusing together to produce

larger nuclei. Heavy nuclei can become more stable by splitting

up to produce fission products of intermediate mass.

Figure 1: Nuclear power from fusion and fission. The graph

shows the excess energy of different nuclei plotted against

atomic mass. The very light atoms have a high excess energy

and can become more stable by fusing together to produce

larger nuclei. Heavy nuclei can become more stable by splitting

up to produce fission products of intermediate mass.

Nuclear Future, Volume 12, Issue 3, May/June 2016 ISSN 1745 2058

Nuclear Future, Volume 12, Issue 3, May/June 2016 ISSN 1745 2058

Figure 2: The three accidents that changed public acceptance of fission power. In a fusion reactor there is no possibility of the

'criticality' at Chernobyl (a), the release of highly active 'fission products' at Three Mile Island (b), or the 'delayed heat' at Fukashima (c)

Figure 2: The three accidents that changed public acceptance of fission power. In a fusion reactor there is no possibility of the

'criticality' at Chernobyl (a), the release of highly active 'fission products' at Three Mile Island (b), or the 'delayed heat' at Fukashima (c)

Figure 3: The ST40 tokamak. The plasma (violet) is the elongated

toroid. The white coils produce the toroidal field along the

direction of the plasma which helps to stabilise it. The blue coils

produce the vertical fields that shape and help form the plasma.

Wound around the brown central column is a solenoid that also

helps drive the plasma current.

Figure 3: The ST40 tokamak. The plasma (violet) is the elongated

toroid. The white coils produce the toroidal field along the

direction of the plasma which helps to stabilise it. The blue coils

produce the vertical fields that shape and help form the plasma.

Wound around the brown central column is a solenoid that also

helps drive the plasma current.

Figure 4:The historical increase in the fusion Lawson 'triple

product'. For three decades until 1997 the fusion triple

product increased exponentially (points and blue line) with

around a two-year doubling time, almost the same as the

Moores's law for semiconductors (red dashed line). Only the

JET and TFTR data points used tritium fuel, the other points

are extrapolations from deuterium plasmas.

Figure 4:The historical increase in the fusion Lawson 'triple

product'. For three decades until 1997 the fusion triple

product increased exponentially (points and blue line) with

around a two-year doubling time, almost the same as the

Moores's law for semiconductors (red dashed line). Only the

JET and TFTR data points used tritium fuel, the other points

are extrapolations from deuterium plasmas.

Figure 5:The recordbreaking shot 42976 on JET. On the right is

a reconstruction of the neutron emission as measured by the vertical

and horizontal neutron cameras [3].

Figure 5:The recordbreaking shot 42976 on JET. On the right is

a reconstruction of the neutron emission as measured by the vertical

and horizontal neutron cameras [3].

Figure 6: Two developments from the 1990s: (left) the START spherical tokamak; (right) the high-temperature

superconducting 'REBCO' tape.

Figure 6: Two developments from the 1990s: (left) the START spherical tokamak; (right) the high-temperature

superconducting 'REBCO' tape.

Figure 7: The Tokamak Energy team at Milton Park.

Figure 7: The Tokamak Energy team at Milton Park.

Figure 8: Our small tokamak with hight-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets, ST25HTS,

hold a plasma for 29 hours, demonstrating the feasibility of HTS for tokamaks.

Figure 8: Our small tokamak with hight-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets, ST25HTS,

hold a plasma for 29 hours, demonstrating the feasibility of HTS for tokamaks.

Figure 9: The figure from the paper by Costley et al. [4]

showing that the fusion gain Qfus is only weakly dependent on

device size R but does depend on the fusion power.

Figure 9: The figure from the paper by Costley et al. [4]

showing that the fusion gain Qfus is only weakly dependent on

device size R but does depend on the fusion power.

Figure 10: On the left is a section through the centre column of a

pilot plant tokamak with a tie-rod (green) in the centre then a high temperature

superconductor alloy (purple), a thermal gap (white) and layers of shield material

(blue) and water-cooling (yellow). On the right is the heat deposition as a function of the thickness of the water-cooling

layer.

Figure 10: On the left is a section through the centre column of a

pilot plant tokamak with a tie-rod (green) in the centre then a high temperature

superconductor alloy (purple), a thermal gap (white) and layers of shield material

(blue) and water-cooling (yellow). On the right is the heat deposition as a function of the thickness of the water-cooling

layer.

Figure 11: A possible modular fusion power plant designed

in collaboration with the Princeton Plasma Physics Institute in

the USA.

Figure 11: A possible modular fusion power plant designed

in collaboration with the Princeton Plasma Physics Institute in

the USA.